Historically, educational publishing formed the bulwark of Canada’s book trade and was fundamental to the success of any publishing house. Textbooks and educational series, which were issued in large numbers, disseminated consistently and widely over many years, consolidated a firm’s broad cultural influence and provided much-needed financial stability in an otherwise risky business.

From the 1920s onward, Book Steward Samuel Fallis and editor Lorne Pierce pursued educational publishing under the Ryerson Press imprint. In fact, for much of the twentieth century the majority of Canada’s large publishing houses were, first and foremost, educational publishers. Individual publishers competed – sometimes unscrupulously – for the opportunity to supply textbooks to the primary and secondary school markets. Those who were successful received lucrative publishing contracts issued by the department or ministry of education of each province. Since these contracts often extended over many years, publishers could rely on stable revenue to sustain their firms and underwrite their less profitable but more prestigious trade publishing programs.

By the close of the 1930s, however, educational publishing had lost some ground. Two key developments caused the declining demand for educational books. First, Canadian teachers were increasingly influenced by the progressive ideas of American educators, such as John Dewey, B.H. Bode, E.L. Thorndike, and A.I. Gates, and they showed a marked preference for American textbooks. As the progressive American educational movement took hold, the clamour for Canadian and British textbooks lessened considerably. Second, in 1936 the province of Ontario, always key since it was “the single largest market for textbooks,”1 undertook curricular revision. For teachers, many of whom were educated in the United States, curricular reform presented a welcome opportunity to adopt American schoolbooks.

At the same time as American influence on Canada’s educational system weakened the demand for Canadian textbooks, ramped up marketing practices by American publishers heightened the appeal of foreign trade books in Canada. Soon, Canadian trade books were regarded as inferior to the many foreign titles in circulation, and the already small audience for local titles was further diminished. Thus, by the end of the decade – with the prospect of war looming – there were fewer profits from both educational and trade sales to cover production costs. This new uncertainty presented a challenge for publishers who had relied on wide and regular sales of educational titles to bolster their companies.

While they were producing schoolbooks, all major Canadian houses also acted as exclusive agents for American and British publishers.2 As George Parker explains, the “agency system” emerged out of historical necessity, since Canada’s relatively small population, and thus readership, often could not support print runs sufficient to offset the high costs associated with publishing and distributing books across a vast country. In order to mitigate these difficulties, Canadian publishers formed agency agreements with foreign publishers. Each agreement provided “an annual commission and a share in the profits from individual sales” of titles that originated with international publishers.3 In return, American and British firms received careful attention from local agents.

As agents, Canadian publishers were at great disadvantage, however. Since Canadian rights were typically ceded as part of “Empire/North American/world rights,”4 foreign publishers often issued Canadian editions, which meant that domestic agents – who were obliged to sell those same editions – were acting against their own publishing interests. They had to market “books they didn’t want” and “had no say in [either] editing or advertising.”5 Moreover, if an agency no longer proved profitable, foreign publishers could cancel their agreements at will. Hence, the agency system made Canadian publishers uncomfortably dependent and highly vulnerable.

As agency sales grew, several American firms established branch plant offices in Toronto and terminated their agreements with Canadian publishers,6 which brought agency publishing to an eventual close. In 1947, for instance, the cancellation of the Doubleday agency – the company had opened a Canadian subsidiary – was devastating to McClelland and Stewart, which lost, according to James King, “half of its sales and more than half of its income.”7 The experience was “a turning point”8 for publisher Jack McClelland. As Judy Donnelly recounts, “he realized the precariousness of the firm’s reliance on foreign agencies, and began to understand that the company had to become more independent, and even more Canadian in its focus.”9

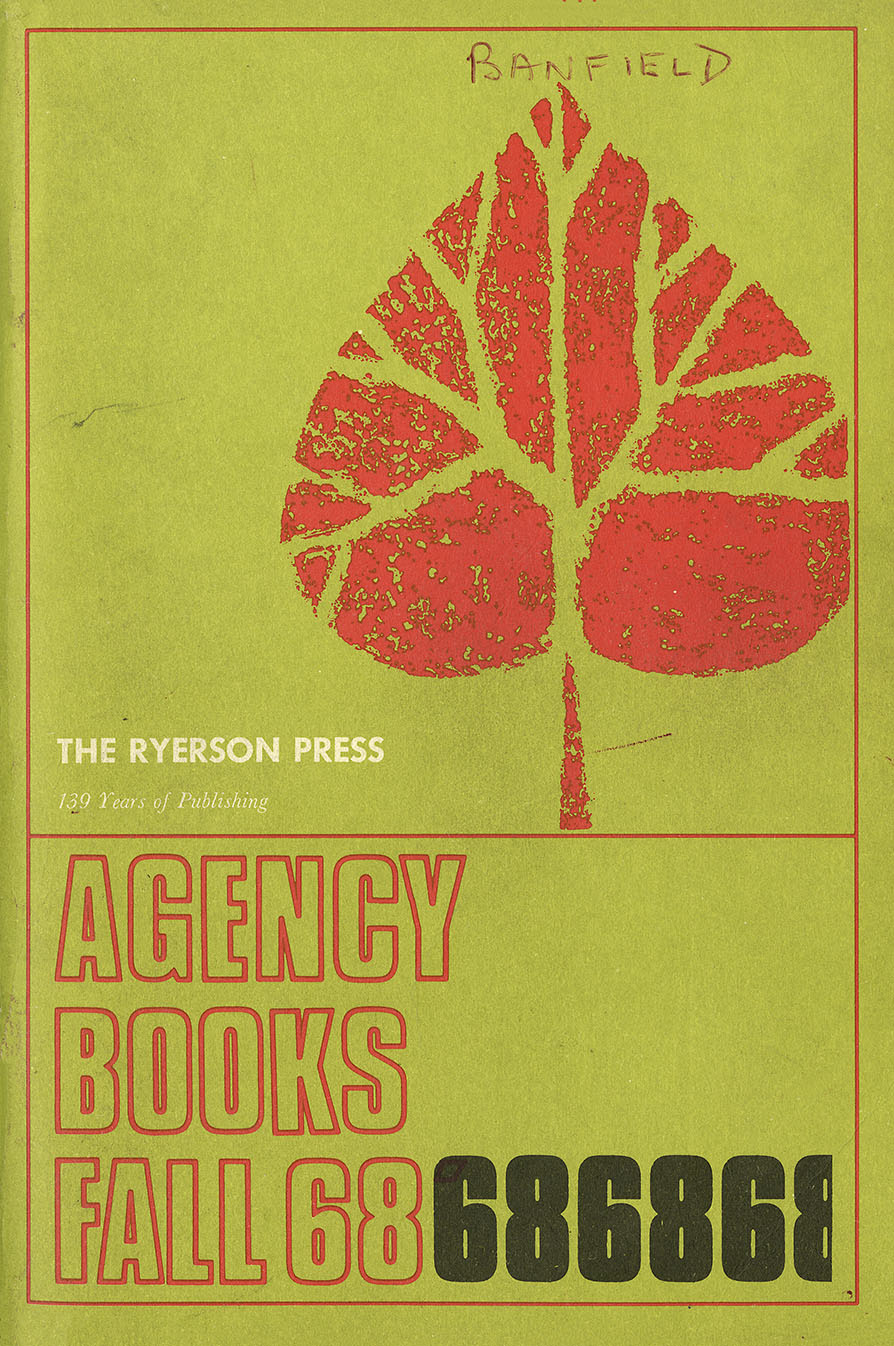

In 1968, however, Ontario’s Ministry of Education delivered two blows that had devastating effects on publishers. First, it cancelled its long-standing program of textbook stimulation grants, which had included designated funding for schoolbook purchases. Then, it authorized an expanded list of textbooks and gave its various school boards new budgetary autonomy. Many, as Penney Clark points out, chose “to divert funds to expenses such as teacher salaries and building maintenance rather than to textbooks.”12 Moreover, since teachers now had greater choice in classroom texts, publishers could no longer count on income generated by strong sales of authorized titles.

Ontario’s actions had serious consequences and by 1970 publishers’ “profits were dropping significantly.”13 Since they had come to rely heavily on textbook sales, companies lost their financial footing and some never fully recovered from the setback. By 1968 and 1969, for example, Ryerson Press “had losses of $572,855 and $626,066.”14 Just one year later, in 1970, the firm was sold to the McGraw-Hill Company.

The sale of Canada’s oldest and highly respected publishing company to an American-owned firm was due, in part, to the elimination of textbook stimulation grants, which radically altered the economics underlying publishing in Ontario. As the first such loss, it was felt deeply by the publishing community and the public at large. It also heralded the future, which saw the demise of most Canadian-owned publishing firms of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and the rise of foreign-owned conglomerates that now dominate the industry.

1 David Young, “The Macmillan Company of Canada in the 1930s,” Journal of Canadian Studies 3.3 (Autumn 1995): 125.

2 Paul Audley, Canada’s Cultural Industries: Broadcasting, Publishing, Records and Film (Toronto: James Lorimer, 1983) 99.

3 George L. Parker, “The Struggle for Literary Publishing: Three Toronto Publishers Negotiate Separate Contracts for Canadian Authors 1920-1940,” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 55.1 (Spring 2017): 8.

4 Parker 9.

5 Parker 9.

6 Roland Lorimer, Ultra Libris: Policy, Technology, and the Creative Economy of Book Publishing in Canada (Toronto: ECW Press, 2012) 84.

7 James King, Jack: A Life with Writers. The Story of Jack McClelland (Toronto: Knopf Canada, 1999) 28.

8 Judy Donnelly, “Jack McClelland and McClelland & Stewart,” Historical Perspectives on Canadian Publishing, McMaster University Library. http://digitalcollections.mcmaster.ca/hpcanpub/case-study/jack-mcclelland-and-mcclelland-stewart.

9 Donnelly.

10 Eli MacLaren, “Canadian Book History,” in The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Literature, ed. Cynthia Sugars (New York: Oxford UP, 2016) 805.

11 See Ruth Panofsky, The Literary Legacy of the Macmillan Company of Canada: Making Books and Mapping Culture, Studies in Book and Print Culture (Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2012).

12 Penney Clark, “‘A Grand Old House’: Canadian Educational Publisher Copp Clark, 1841-2004,” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 55.1 (Spring 2017): 86.

13 Clark 86.

14 George L. Parker, “The Sale of Ryerson Press: The End of the Old Agency System and Conflicts over Domestic and Foreign Ownership in the Canadian Publishing Industry, 1970-1986,” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 40.2 (Fall 2002): 9. See also Ruth Bradley-St-Cyr, “The Downfall of the Ryerson Press,” PhD dissertation, U of Ottawa, 2014.