“[W]E had felt the need of a Press at our command, not only to explain our doctrines and polity, but more especially to fight the battles in which we were engaged for equal rights and for religious equality.”1 So stated the Reverend Anson Green (1801-1875) in his memoir of 1877, in a passage in which he recalls the tempestuous political and sectarian environment of Upper Canada in the early nineteenth century. The “we” to whom he refers was the membership of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada. In 1828, this Upper Canadian Methodist community sought and achieved a status independent of the American Methodist Episcopal Church with which it had always been affiliated. In the wake of the War of 1812, this group of Upper Canadian Methodists had been increasingly subject to hostility because of their relationship with the American church.

That hostility found particular voice in a sermon given by Anglican Bishop John Strachan (1778-1867) in 1825. The sermon appeared in print in 1826 and circulated widely. Strachan characterized Methodist ministers as “uneducated itinerant preachers, who leaving their steady employment, betake themselves to preaching the Gospel from idleness, or a zeal without knowledge.”2 He further accused them of “spreading disaffection to the civil and religious institutions of Great Britain.”3 A young Methodist minister, Egerton Ryerson (1803-1882), responded to this slur on the competence and loyalty of his brethren. He wrote a lengthy letter that appeared on 11 May 1826 in the Upper Canadian newspaper The Colonial Advocate. Ryerson’s letter, among other things, accused Strachan of “slander, bigotry, [and] ignorance.”4 It was reprinted in pamphlet form and further circulated.

In 1829, a year after ending its affiliation with the American church, the Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada decided to establish a weekly denominational newspaper “under the direction of the [church] Conference, of a religious and moral character, to be entitled the ‘Christian Guardian.’”5 Egerton Ryerson was elected founding editor, winning by just one vote over two other ministers. Published at York (later Toronto), the first issue of the paper appeared on 21 November 1829.

Alongside its decision to launch a denominational newspaper, the Conference had also decreed that printing equipment be purchased. As one of his first acts as editor, Ryerson went to New York to purchase $700 of printing equipment. The Conference’s decision to purchase a press to print its newspaper, rather than simply seek the services of an Upper Canadian printer, was a signal of larger ambitions. Within a month of the first issue of its denominational paper, the Guardian office began to advertise commercial printing services. Within a year, the Guardian office also offered for sale an assortment of religious works issued by book publishers, including some produced by the UK-based British and Foreign Bible Society.

In creating a combined printing-publishing-bookselling operation, the Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada took an approach to the printing, publishing, and bookselling trades typical of colonial British North America. Limited population and literacy made it wiser to offer a range of complementary services in order to sustain a business. However, a combined operation of this type also resided firmly within a transplanted Methodist tradition of publishing and disseminating religious print. This tradition dated back to the eighteenth-century British origins of the Protestant denomination.

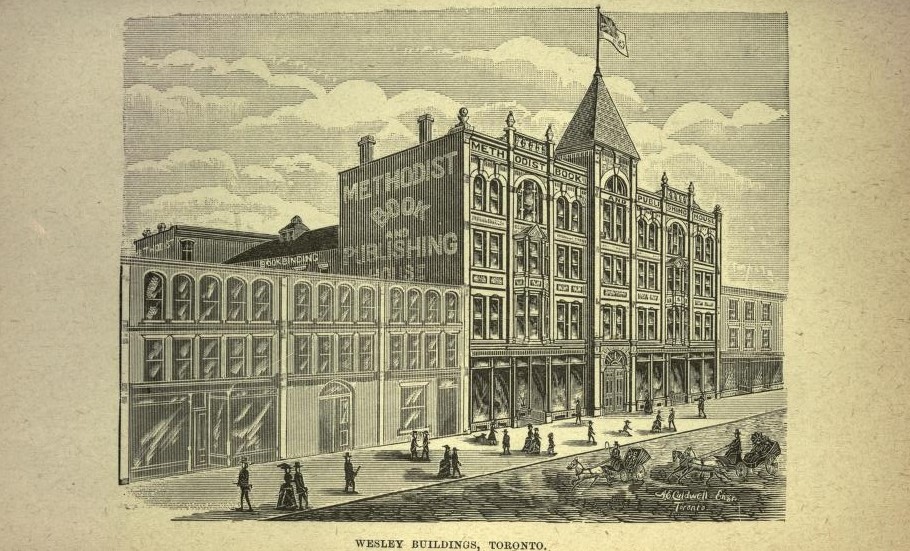

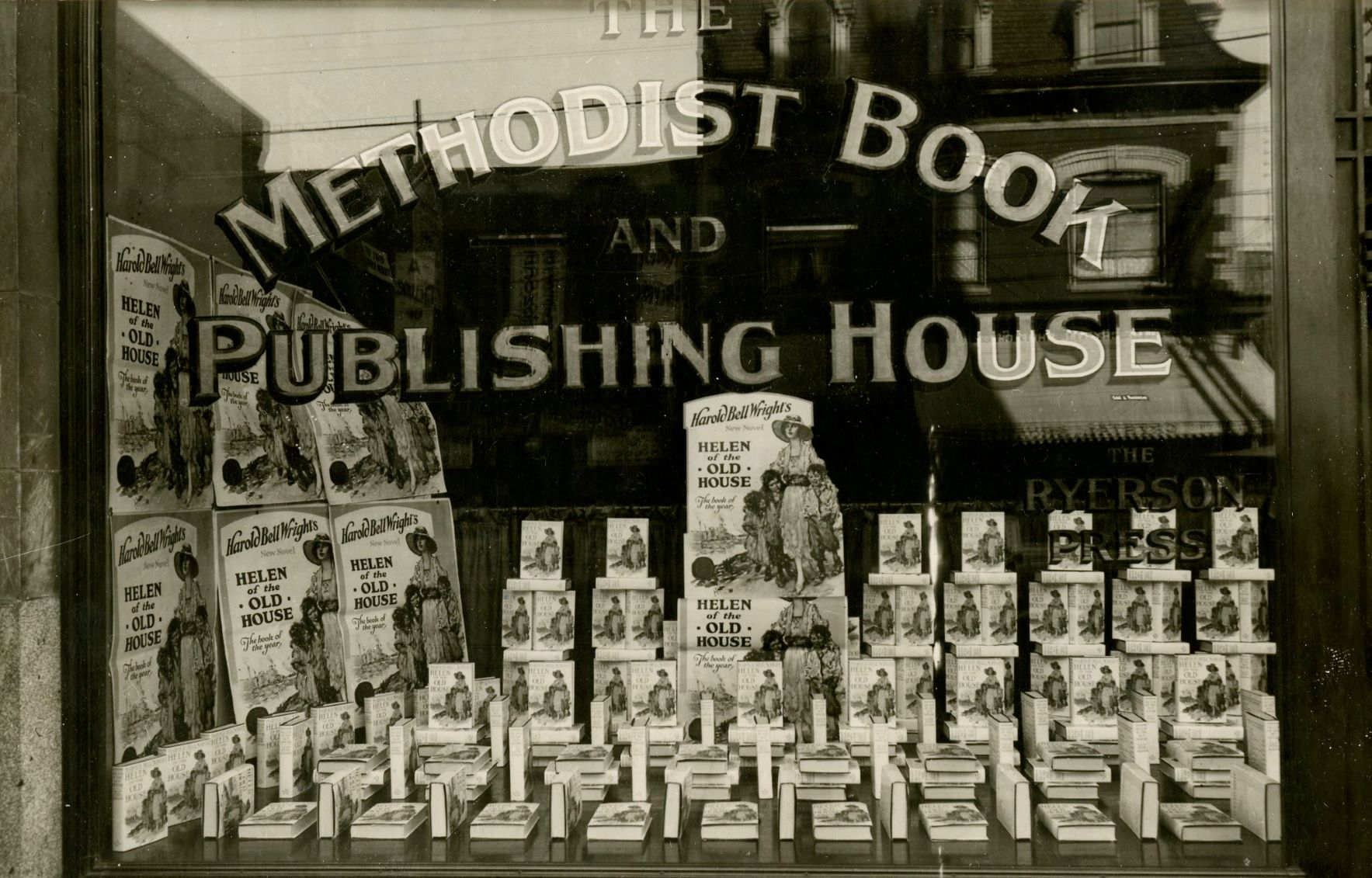

Initiated by John Wesley in the late 1730s, early Methodism emphasized a personal relationship between the individual and God. As part of his religious work, Wesley soon began publishing and disseminating educational and spiritually illuminating tracts which were sold cheaply to followers. By 1739, Wesley had established what he called a “Book Room” for the publications disseminated to his community. This commitment to disseminating religious print materials migrated with Methodism to North America, and the phenomenon of Book Rooms subsequently appeared first in the US and then in British North America. When the Canadian Conference of the church met in October 1833, it formally resolved to establish a book depository at York that would hold books acquired from Great Britain and the UK.6 This “Book Room” was initially placed under the charge of the Guardian’s editor. That same year, the Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada merged with the British Wesleyans active in Upper Canada to form the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada.7 The British Wesleyans of Lower Canada joined this union in 1854. After Confederation in 1867, when an imperative to form a dominion-wide church emerged, a subsequent merger in 1874 would produce the Methodist Church of Canada.8 At that point, the combined printing, publishing, and bookselling operations of the merged churches became known as the Methodist Book and Publishing House.

The four decades prior to the 1874 church union witnessed significant expansion and diversification of the Wesleyan Methodists’ printing, publishing, and bookselling operations. By 1835, the demands of the organization had grown sufficiently to justify the dedicated energies of two clergyman, and so a second office of Book Steward was created to work in tandem with the Editor. Their efforts were overseen by a Book Committee which, from 1833 to 1874, was comprised of Toronto and area ministers. Following the Methodist tradition established by Wesley, all clergy of the church served as agents for the publications issued or offered for sale by the operation.

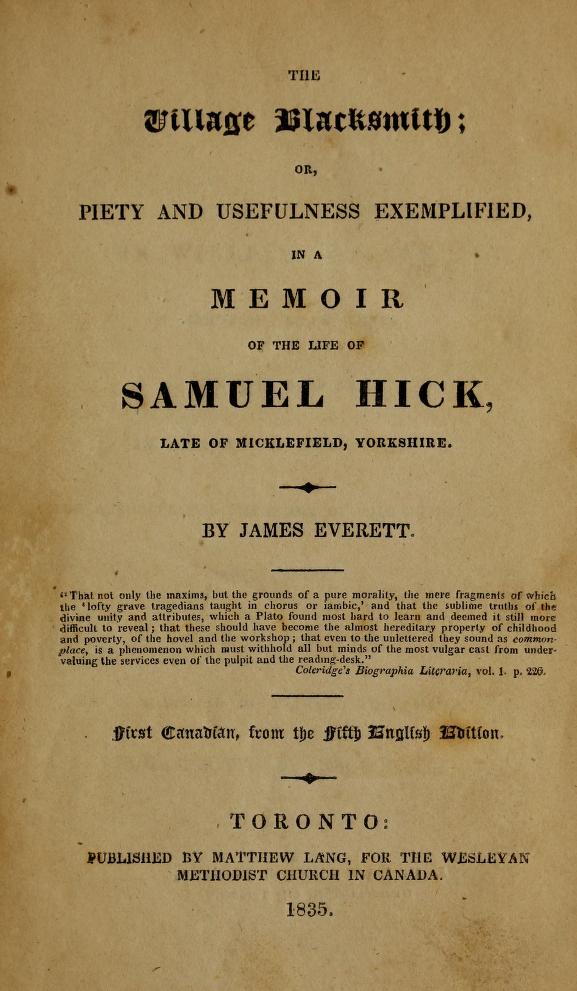

In terms of publishing activity, these decades also saw early efforts in relation to Sunday School papers, the first instance being the Sunday School Guardian, launched in January 1846. Book publishing commenced with the Doctrines and Discipline of the Methodist Church of Canada (1829). In general, book and pamphlet publishing during these decades comprised a modest number of works produced as print jobs for other organizations or individuals. Some were financed by means of subscription, the financial risks of publishing for such a small colonial market being quite severe. One early anomaly appears to be a distinctly Canadian edition of James Everett’s biography The Village Blacksmith; or, Piety and Usefulness Exemplified, in a Memoir of the Life of Samuel Hick (1835), which was produced in a print run of 1000 copies and interspersed by its Canadian editor, Reverend W. Lord, “with interesting notes.”9 The Village Blacksmith recognized the life and contributions of a British Methodist minister. However, by the middle of the nineteenth century, some interesting initiatives around a Methodist Canadian literature began to appear in book form. These efforts would be augmented starting in the mid-1870s by the launch of the Canadian Methodist Magazine. The magazine was introduced during Samuel Rose’s tenure as Book Steward from 1865 to 1879. As Book Steward, Rose expanded the entire enterprise in more commercial directions, widening the range of titles both imported and published. Moreover, following the formation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867 and the Methodist union in 1874, the Methodist Book and Publishing House became more national in orientation. This trend gained even greater impetus in 1884, when there was yet another Canadian union of Methodists, this time to form The Methodist Church.10 This final denominational union rendered The Methodist Church the largest Protestant denomination in Canada.

1 Anson Green, The Life and Times of the Reverend Anson Green (Toronto: Methodist Book Room, 1877) 134-35.

2 John Strachan cited in William Westfall, Two Worlds: The Protestant Culture of Nineteenth-Century Ontario (Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP) 24.

3 Egerton Ryerson, The Story of My Life, ed. J. George Hodgins (Toronto: William Briggs, 1883) 48.

4 Westfall 24.

5 Minutes of the Conference, 1829. The Minutes of the Annual Conferences of the Wesleyan-Methodist Church in Canada from 1824 to 1845, inclusive; with many official documents and resolutions not before published (Toronto: Anson Green, Conference Office, 1846) 27.

6 Minutes of Conference, 1833. The Minutes of the Annual Conferences of the Wesleyan-Methodist Church in Canada from 1824 to 1845, inclusive, 57-58.

7 The union was contentious and tempestuous. An alienated portion of the original Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada’s membership immediately struck out on its own, retaining the original name. The membership of the merged Upper Canadian groups had difficulty getting along, leading to a break up in 1840 that lasted until 1847, when the factions reunited.

8 The Methodist Church of Canada of 1874 was the result of the merger of Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada with the Conference of Eastern British American and the Methodist New Connexion Church.

9 Lorne Pierce, The House of Ryerson (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1954) 10 and “Just Published The Village Blacksmith,” Christian Guardian 28 October 1835.

10 The 1884 union merged the Methodist Church of Canada with the Primitive Methodist Church of Canada, the Bible Christian Church in Canada, and the Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada (i.e. the breakaway church from the original 1833 union of Upper Canadian Methodists).