The Ryerson Fiction Award, also known as the All-Canada Fiction Award, was part of an attempt by Lorne Pierce, general editor of Ryerson Press, to create a strong fiction list.1 Awarded irregularly between 1942 and 1960 to a new or emerging writer from anywhere in Canada,2 it offered a cash prize of $1000 to the winner: $500 as an outright prize upon presentation of the Award, as well as an additional $500 as an advance on royalties.3 Ryerson Press published all winning manuscripts.

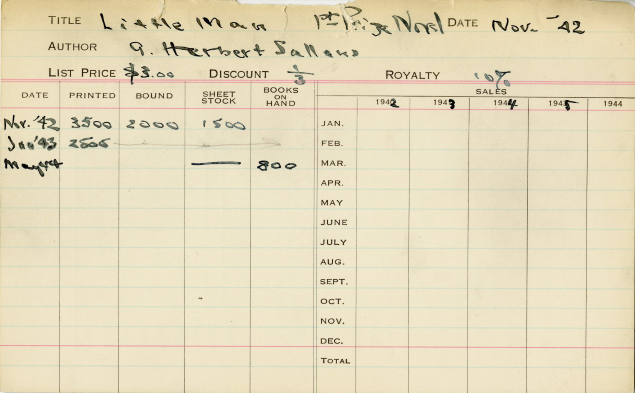

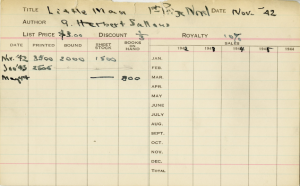

Manuscripts had to be between 50,000 to 100,000 words in length.4 The winner was chosen based on creativity and expertise, by a panel of three judges, whose members often were selected for sharing the same conservative values as Pierce, such as Montreal Star book editor Samuel Morgan-Powell.5 Works of mystery or adventure were ineligible for the Award, an example of the disdain of contemporary literary elites for works of genre fiction.6 Typically, the initial print run of each award-winning title was three to 5000 copies, and only three of the thirteen prizewinners were popular enough to warrant a reprint.7

Although more than 100 manuscripts were submitted in 1942, the contest was eventually closed due to dwindling popularity and increasing competition; in the same period, for example, the New York-based Doubleday offered $10,000 USD for a work of outstanding fiction.8 Nonetheless, the Ryerson Fiction Award proved to be an excellent way to discover and assist the development of Canadian writers, as not only did Ryerson publish the winning titles, the firm also issued some of the other submissions.9

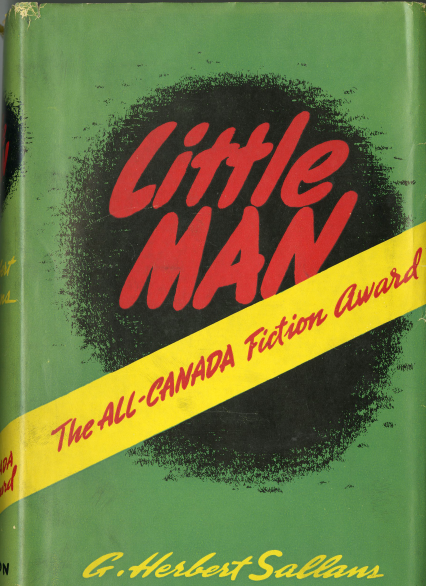

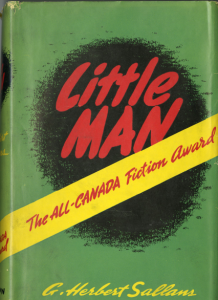

The first winner, in 1942, was G. Herbert Sallans for Little Man.10 Sallans was a general news manager for the Canadian United Press, and before that served as managing editor of the Vancouver Sun from 1930 to 1941.11 He was born in Ontario, moved to Saskatchewan with his family when he was eight, and published his first short story at age thirteen.12 He continued to engage in journalism as he matured, acting as a correspondent for several weekly publications while studying at Wesley College, Winnipeg.13 He then left college to enlist in the Canadian field artillery and served with it until the end of the First World War, before returning home to pursue a career in journalism. His novel, Little Man, is heavily shaped by personal experience. It follows a Canadian, named George, who is demobilized after the war, moves out West, and recounts his experiences until the start of the Second World War. In the book, Sallans reveals the unique terrain of the Prairies at the height of their development and during the 1912 and 1913 depression, commenting on Canadian identity in the process.14 The novel was well received; it appealed to a wide readership and won the Governor General’s Literary Award.15

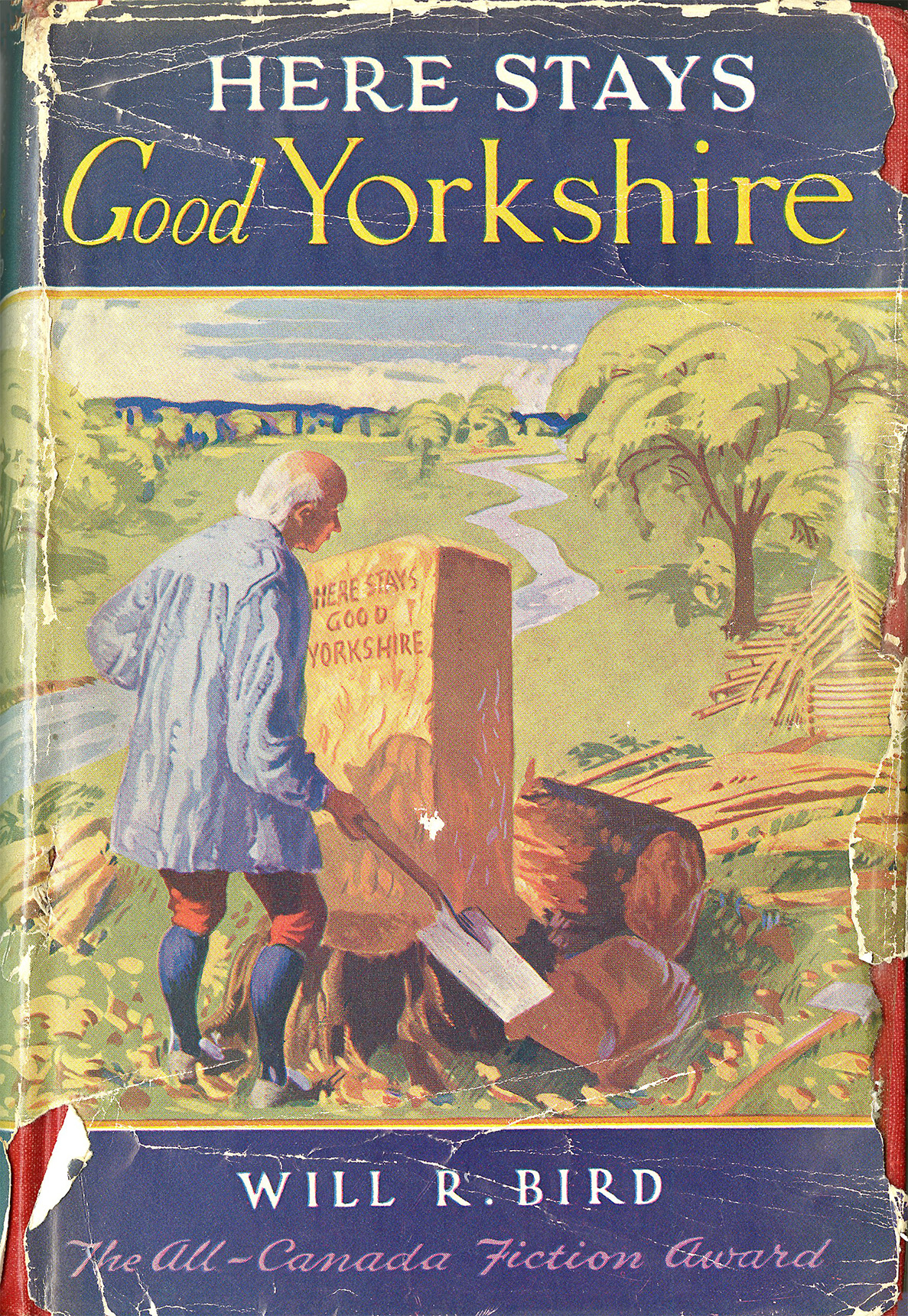

In 1945, the Award was shared by Philip Child’s Day of Wrath and Will R. Bird’s Here Stays Good Yorkshire. Born in Hamilton, Child enlisted as a subaltern in the First World War and later pursued a career in journalism in New York, before becoming an English professor at Trinity College.16 He was also an editor of the University of Toronto Quarterly.17 Day of Wrath tells the story of Jewish persecution in Nazi Germany.18 It begins as a love story between Simon Froben, a Jewish man, and Anna Huber, an Aryan woman.19 The novel takes several dark turns, however, and ends tragically with Froben’s execution by firing squad after he rescues a child, and Huber’s death by suicide after she goes insane. The story serves as a potent reminder of youthful idealism, which is juxtaposed with the racial hatred of Nazi Germany.20 Since it lacked a Canadian element, Day of Wrath was not particularly well received.21

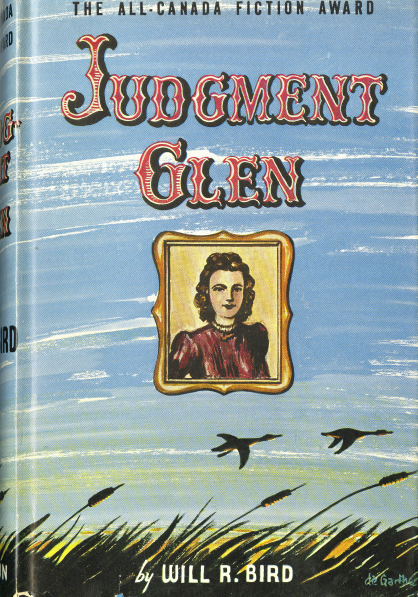

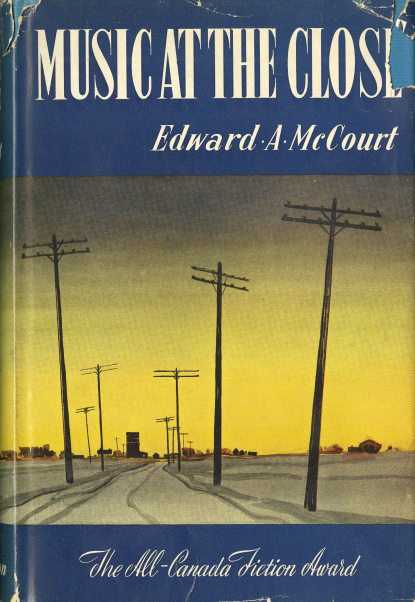

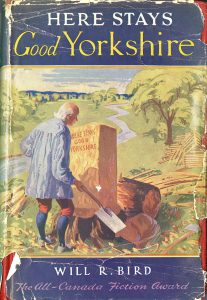

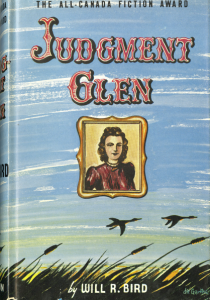

Novelist Will R. Bird was born in Nova Scotia and served with the 42nd Royal Highlanders in the First World War.22 Upon his return to civilian life, he worked briefly as a lecturer, touring all across Canada, before moving to Halifax and working at the Nova Scotia Bureau of Information from 1933 to 1950.23 He also served as president of the Canadian Authors Association from 1949 to 1950.24 Despite his busy career, he was a prolific writer. Bird’s Here Stays Good Yorkshire tells the story of Yorkshire settlers who emigrated to the Chignecto Isthmus on the Nova Scotia-New Brunswick border in the 1770s, but the novel was criticized for its lack of organization, a problem which Bird resolved in Judgment Glen.25 Judgment Glen focuses on the Fallydown family after their move to the Cumberland Region and outlines the conflict between a wife, her cruel husband, and their three children. Both of Bird’s books emphasized atmosphere over the contemporary stress on strong characters.26 Judgment Glen tied with Edward McCourt’s Music at the Close for the Ryerson Fiction Award in 1947.27

Born in Ireland, McCourt graduated from the University of Alberta. He was a Rhodes Scholar and later a professor of English at the University of Saskatchewan.28 Music at the Close follows the development of Neil Fraser, an orphan who becomes a good student and a local baseball hero who finds love.29 The book then turns tragic as the good things in Fraser’s life are stripped away: his friends, wife, money, and land. Fraser dies on a beach in Normandy during the Second World War, alone but comforted by the knowledge that his son will know his father died a sergeant. It was a strong work of social criticism that warned about the effects of societal conditions on youth.30

Philip Child won the Award a second time in 1949 for Mr. Ames against Time, about the murder of the owner of a burlesque theatre.31 A professor, Mr. Ames accidentally convicts his son Mike with his testimony and then spends the majority of the narrative attempting to convince the two other suspects to confess. It was a serious approach to an action story, with a strong focus on psychology and morality, and held strong emotional appeal for the public.32 The novel won the Governor General’s Literary Award.33

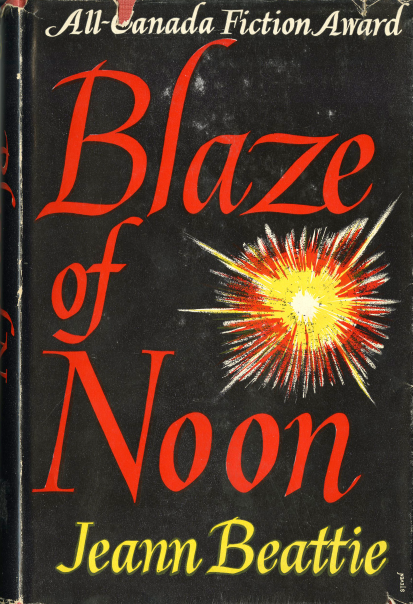

In 1950, the Award went to Jeann Beattie for Blaze of Noon, making her the first woman and, at age 28, the youngest writer to win.34 Beattie began working for the St. Catharines Standard newspaper at age eighteen, before deciding to pursue her first degree in journalism from Columbia University, followed by a degree in political science from the New School of Social Research.35 She later worked as a writer for Maclean’s and as a producer at the CBC.36 Blaze of Noon tells the tale of two girls who leave their jobs at a small newspaper in Southern Ontario and move to New York City to pursue a life of adventure.37 In New York, the end of the Second World War and the rise of communism impact their lives. Though Beattie received a great deal of praise for her book, one critic found fault with the “increasingly irksome” dialogue between the characters.38

The next winner, in 1953, was Evelyn Richardson for Desired Haven. Richardson attended high school in Halifax, earned a BA from Dalhousie University, and went on to become a teacher.39 On Bon Portage Island, Nova Scotia, she and her husband worked as lighthouse keepers for thirty-five years.40 Desired Haven is a nineteenth-century tale about a seaman’s daughter who falls in love with Dan, a man rescued by her father.41 Rather than leave once he has recovered, Dan decides to abandon his plans to go to Boston and instead pursues a relationship with the seaman’s daughter. Intrigue arises when Dan turns to smuggling and the seaman’s daughter turns against her lover. The novel was so popular it was bought as a serial by Farm Magazine and chosen by the People’s Book Club (of Sears-Roebuck) as its March selection, although there is some confusion as to whether or not the order was later cancelled.42

Laura Goodman Salverson won the Award in 1954 for Immortal Rock. Salverson was born the daughter of Icelandic immigrants and, though she learned English later, Nordic culture played a large role during her formative years and influenced her writing.43 Her education was frequently disrupted by the need to work and help support her family. After working in various capacities, she married in 1913 and travelled frequently across Western Canada with her husband. Immortal Rock is based on a story inscribed on the Kensington Stone, a rock discovered in Minnesota in 1898, which tells of a fictitious fourteenth-century expedition by Norse explorers. The book focuses on the survivors’ last day. Salverson was lauded for writing novels with strong characters and well-developed plots and settings.44

Gladys Taylor won the Award twice, for Pine Roots in 1956 and The King Tree in 1958. Taylor was born in Swan River, Manitoba, educated in Winnipeg, and returned to Swan River to teach.45 In 1940, she married a soldier who, one year later, was posted overseas. Taylor joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) in 1943 and eventually was posted to Regina as the writer responsible for all CWAC publicity in Saskatchewan. In 1945, both she and her husband were discharged from the army. Between 1945 and 1960, the year they divorced, Taylor published the novels that won her Ryerson Fiction Awards. The first, Pine Roots, tells of a young couple that settles in northern Manitoba, while the second, The King Tree, follows two families caught up in the Papineau Rebellion.46 The second novel earned a scathing comment from a writer in Queen’s Quarterly: “If this is the ‘All-Canada Fiction Award’ as the dust cover asserts, it has been a slim year for the novel, or at least for the publisher who has the presumption to imply that this is the best work of fiction published in Canada in the past year.”47 Criticism, however, did not deter Taylor and she continued working in journalism, later starting her own newspaper.48

In 1957, the Award went to Joan Walker, author of the novel Repent at Leisure. Walker was born in England and attended various schools before working as an editor and freelance writer in London throughout the Second World War.49 She married a soldier in 1946 and moved to Canada. Repent at Leisure tells the tale of a woman who marries a soldier from Quebec, only to find out when she arrives in Canada that he has deceived her about his identity. The wife tries nonetheless to make the union work and what follows is a comic account of the trials and tribulations of her marriage, before it ends in divorce. The novel was described in the Globe and Mail on 7 December 1957 as “refreshing,” “original, contemporary, credible, and readable,” and “to be admired.”50

Arthur G. Storey won the Award in 1959 for his book Prairie Harvest. Storey was born in Saskatchewan and served overseas during the Second World War.51 After the war, he graduated from the University of Saskatchewan and then earned a PhD from Stanford University. He later joined the Faculty of Education at the University of Calgary, becoming a professor and entrepreneur. Prairie Harvest recounts the adventures of a family living in Saskatchewan and ends on an optimistic note with the farmer certain that the current harvest would be good.52 It was criticized for being racist and boring.53

The final Award winner in 1960 was E.M. Granger Bennett for her novel Short of the Glory. Bennett was born in England and raised in Collingwood, Ontario, where she attended Collingwood Collegiate Institute.54 She earned a BA in modern languages from Victoria College, Toronto and a PhD in French literature from the University of Wisconsin, Madison.55 She taught at several different establishments and continued writing historical fiction throughout her career. Short of Glory is set in New France in the 1760s, when the English and the French are struggling for control of the fur trade.56 An English girl is captured by Natives, then ransomed by the French, and lives as a prisoner and friend in the household of the Intendant, a high-ranking French official. The girl is wary of French society, until she meets and marries a French voyageur, effectively assimilating.

Between 1942 and 1960, the Ryerson Fiction Award helped to foster the careers of Canadian authors. These men and women came from a wide variety of backgrounds and brought differing approaches to fiction, but they were united in their passion for writing. Many were trendsetters and often went on to win other awards.

1 Brian Busby, “Anyone Care about the Ryerson Fiction Award?” Dusty Bookcase 7 January 2013. http://brianbusby.blogspot.com/2013/01/anyone-care-about-ryerson-fiction-award.html; Sandra Campbell, Both Hands: A Life of Lorne Pierce of Ryerson Press (Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2013).

2 “Ryerson Press Fiction Award Contest Opens,” Winnipeg Tribune 27 June 1944. Accessed 13 September 2018, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/893010/the_winnipeg_tribune.

3 “Toronto Novelist Wins Ryerson Award,” Ottawa Journal 21 May 1949. Accessed 13 September 2018, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/892986/the_ottawa_journal.

4 “Ryerson Press Fiction Award Contest Opens.”

5 “Ryerson Press Fiction Award Contest Opens”; “G. Herbert Sallans, Newspaperman, Wins Ryerson $500 Fiction Prize,” Globe and Mail 9 May 1942. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1350869623?pq-origsite=summon; Campbell.

6 “Ryerson Press Fiction Award Contest Opens.”

7 Ryerson Press Author Contract with G. Herbert Sallans (Little Man), November 1942; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Philip Child (Day of Wrath), November 1945; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Will R. Bird (Here Stays Good Yorkshire), December 1945; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Will R. Bird (Judgment Glen), November 1947; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Edward A. McCourt (Music at the Close), November 1947; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Philip Child (Mr. Ames against Time), October 1949; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Jeann Beattie (Blaze of Noon), 29 September 1950; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Evelyn M. Richardson (Desired Haven), 17 April 1953; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Laura Goodman Salverson (Immortal Rock), October, 1954; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Gladys Tall Taylor (Pine Roots), September, 1956; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Mrs. Lorne (Gladys) Taylor (The King Tree), October, 1959; Ryerson Press Author Contract with Arthur G. Storey (Prairie Harvest), 1959; Ryerson Press Author Contract with E.M. Granger Bennett (Short of the Glory), September 1960, Archives and Special Collections, Ryerson University Library.

8 Lyn Harrington, Syllables of Recorded Time: The Story of the Canadian Authors Association 1921-1981 (Toronto: Simon and Pierre, 1981) 261; “Ryerson Press Fiction Award Contest Opens.”

9 “Ryerson Fiction Award,” Globe and Mail 15 June 1946. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search- https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1291213094/98C34449866440C1PQ/27?accountid=13631.

10 “G. Herbert Sallans.”

11 “G. Herbert Sallans.”

12 “G. Herbert Sallans”; “Little Man. First Printing in Dust Jacket — SALLANS, G. Herbert,” John W. Doull, Bookseller, Inc. Accessed 10 October 2018, http://www.doullbooks.com/?page=shop/flypage&product_id=117240.

13 “G. Herbert Sallans.”

14 “G. Herbert Sallans.”

15 “Governor-General’s Literary Awards Winners,” Globe and Mail 3 June 1950. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1313866190/7E88720CEE4F4864PQ/3?accountid=13631.

16 “Governor-General’s Literary Awards Winners.”

17 “Governor-General’s Literary Awards Winners”; “Child, Philip, 1898-1978, LMS-0011,” Library and Archives Canada. Accessed 10 October 2018, https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/literaryarchives/027011-200.029-e.html.

18 “Governor-General’s Literary Awards Winners.”

19 William Arthur Deacon, “Nazi Jew-Baiting Theme of Ryerson Prize Novel,” Globe and Mail 1 December 1945. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1316238976/465CAFE467354659PQ/3?accountid=13631.

20 Deacon, “Nazi Jew-Bating Theme.”

21 Deacon, “Nazi Jew-Baiting Theme.”

22 Marlene Alt, “Will R. Bird,” Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/will-r-bird.

23 Alt, “Will R. Bird.”

24 Alt, “Will R. Bird.”

25 Alt,“More Yorkshire Pioneers Settle at Ft. Cumberland,” Globe and Mail 8 November 1947. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1323425555/6BA683775E25449CPQ/2?accountid=13631.

26 Alt, “More Yorkshire Pioneers.”

27 Alt, “More Yorkshire Pioneers.”

28 “A Tragedy of Maladjustment in Drought-Stricken Alberta,” Globe and Mail 29 November 1947. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1313846524/D1A626BA022048E8PQ/4?accountid=13631; “Will R. Bird and Edward A. McCourt Divide Ryerson 1947 Fiction Award,” Globe and Mail 10 May 1947. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1323614519/D1A626BA022048E8PQ/7?accountid=13631.

29 “A Tragedy of Maladjustment.”

30 “A Tragedy of Maladjustment.”

31 William Arthur Deacon, “With Reluctant Self-Sacrifice Murderer Clears Innocent Man,” Globe and Mail 1 October 1949. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1291533880/7E88720CEE4F4864PQ/1?accountid=13631.

32 Deacon, “With Reluctant Self-Sacrifice.”

33 “Governor-General’s Literary Awards Winners.”

34 Matthew Van Dongen, “‘She had the most fantastic intellect,’” St. Catharines Standard [Final ed.] 23 September 2005. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/349822005?pq-origsite=summon.

35 Joan Hotson and Gail Benjafield, “Lives Lived: Jeann Beattie,” Globe and Mail 8 March 2006. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1400820194?pq-origsite=summon.

36 Hotson and Benjafield.

37 Claude T. Bissell, “Fiction,” University of Toronto Quarterly 20.3 (1951): 262-72.

38 Bissell; William Arthur Deacon, “The Fly Leaf,” Globe and Mail 4 November 1950. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1287595923?pq-origsite=summon.

39 “Meet Evelyn Richardson,” Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia 3 April 2018. https://www.writers.ns.ca/blog/meet-evelyn-richardson.html.

40 “Meet Evelyn Richardson.”

41 “Kirkus Review,” Kirkus. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/evelyn-m-richardson/desired-haven/.

42 William Arthur Deacon, “The Fly Leaf,” Globe and Mail 14 November 1953. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1287755621?pq-origsite=summon.

43 “Laura Goodman Salverson,” Contemporary Authors Online. http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/ps/i.do?p=LitRC&u=rpu_main&id=GALE%7CH1000086702&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon.

44 “Laura Goodman Salverson.”

45“Ryerson Novel Award, 1956, Introduces Gladys Taylor,” Globe and Mail 21 April 1956. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1291274889?pq-origsite=summon.

46 “Gladys Taylor, 1917-2015: A Life Well Lived,” Smoky Lake Signal 3 June 2015. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1686003050?pq-origsite=summon; “The King Tree by Taylor, Gladys,” Biblio.co.uk., https://biblio.co.uk/the-king-tree-by-taylor-gladys/work/2444609.

47 Busby.

48 “Gladys Taylor, 1917-2015.”.

49 “Joan Walker,” Canadian Literary Humorists. http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/ps/i.do?p=LitRC&u=rpu_main&id=GALE|H1200014266&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon.

50 “Joan Walker.”

51 Arthur G. Storey, Prairie Harvest (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1959).

52 George Melnyk, The Literary History of Alberta. Volume Two: From the End of the War to the End of the Century (Edmonton: U of Alberta P, 1998).

53 Douglas Forrester, “Publishers’ Prize-Day,” Review of Prairie Harvest, by Arthur G. Storey; and Black Angels, by D.T. Ritchie, Canadian Literature 3 (Winter 1960): 79-80.

54 “Ethel Mary Granger Bennett,” fonds 32, Special Collections, E.J. Pratt Library, Victoria University in the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario. Accessed 20 September 2018, https://library.vicu.utoronto.ca/collections/special_collections/f32_ethel_mary_granger_bennett.

55 “Ethel Mary Granger Bennett.”

56 Joan Selby, “Chronicle and Creation,” Review of Short of the Glory, by E.M. Granger Bennett, Canadian Literature 8 (Spring 1961): 73-74.