When Lorne Pierce became editor of Ryerson Press, he understood both the economic and cultural value of publishing educational material. Although he focused first on textbooks for use in schools, he did not ignore the market for instructional works in the home. One publication that straddled both spheres was the Canadian Cook Book. Pierce believed that the “conventional Canadiana”1 aspect of the publication would tap into a growing sense of nationalism, and he was not wrong. For decades, as Susan Goldenberg recalled in 2005, the bestselling Canadian Cook Book was used widely in educational institutions and modern homes alike.2

Though Pierce encouraged production of the Canadian Cook Book, Nellie Lyle Pattinson was at the helm of the project. Pattinson was born on 24 October 1878 in Bowmanville, Ontario. After graduating from the University of Toronto in 1907, Pattinson applied the knowledge she had gained from her household science program to her position as instructor of physiological chemistry at the University of Toronto.3 Pattinson left the position in 1915 for an opportunity to teach at Central Technical School, one of the first educational institutes of its kind in Toronto. By 1920, she had become the school’s director of domestic science. A leader in her field, Pattinson was the ideal candidate to bring the Canadian Cook Book to life.

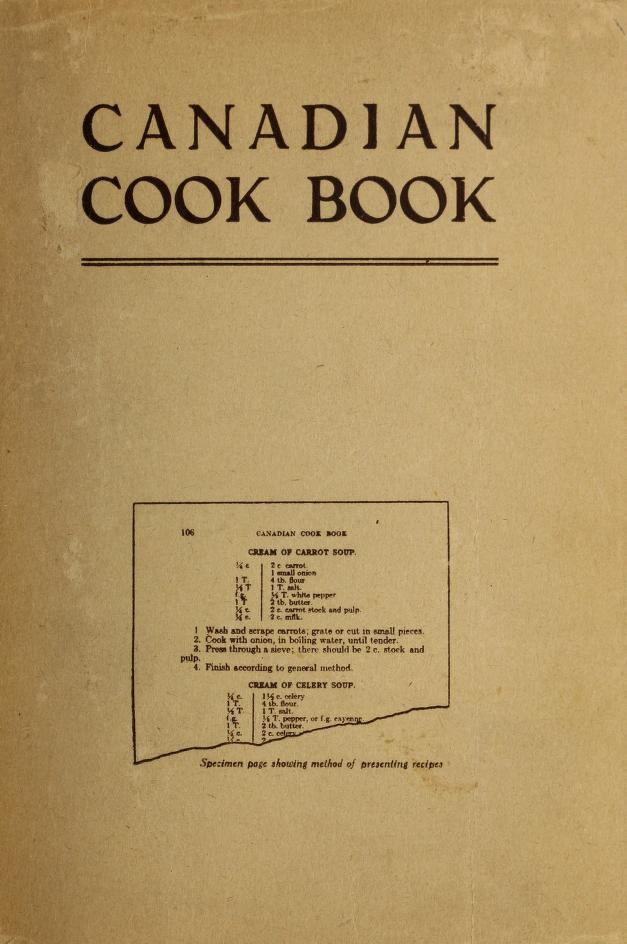

The first edition of the Canadian Cook Book was published in 1923. Its simple design and plain blue cloth binding – which remained unchanged until its revision in 1953 – gave rise to the nickname the “Blue Cookbook.”4 The first edition sold for $1.50 and Pattinson received a high 15% royalty on sales.5 Although it featured few photographs, the book contained numerous recipes and other informative sections. The first chapter, Food and Its Use, defined protein, fat, and carbohydrates, and offered instruction on the principles of healthy eating.6 In fact, information on healthy eating practices appeared as part of the work throughout the Canadian Cook Book’s history; not only did it tell readers how to make meals, it told them which meals to prepare. These recommendations reflected recent significant advances in nutritional science.

The Canadian Cook Book was very much of its time. Chapters included information about making large quantities of food, as well as rules of etiquette for serving food to guests. These recommendations arose from a culture of women preparing meals for large family gatherings and church suppers. A chapter on food preparation for invalids was also included, indicating the fact that sick family members often were cared for in the home.

After decades of success, Ryerson Press felt the need to update and modernize the Canadian Cook Book. Since Pattinson, by then in her seventies, did not feel up to the task, Ryerson Press engaged Helen Wattie and Elinor Donaldson Whyte as co-editors to oversee the revision process. Wattie was born in 1911 in Bracebridge, Ontario. After graduating from the new home economics program at the University of Toronto, she served as vice-principal for Kirkland Lake Collegiate and Vocational Institute from 1943 to 1950.7 She went on to head the home economics department at Ryerson Institute of Technology (now Ryerson University) from 1950 to 1955.8 In 1968, she published the popular Home Management and Nutrition (Toronto: General Publishing).9 Donaldson Whyte was a fellow University of Toronto graduate and, from 1952 to 1953, also taught at Ryerson.10

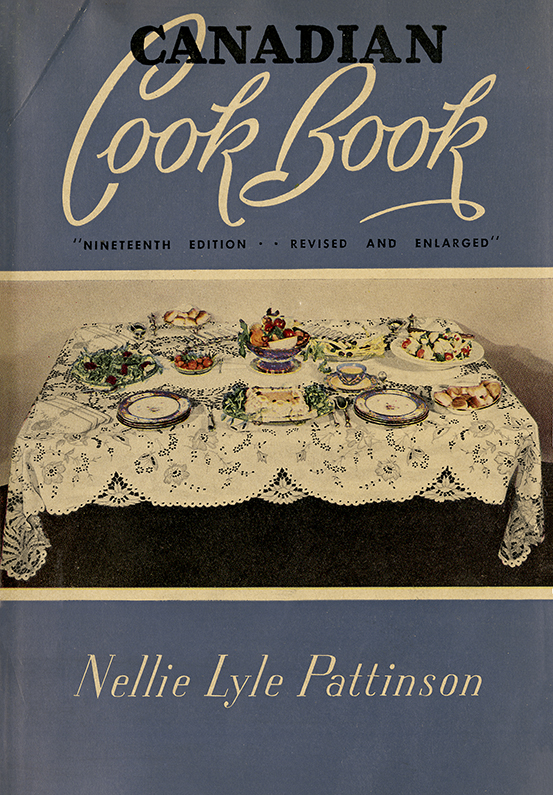

In 1953, the second edition of the Canadian Cook Book was published under the direction of Wattie and Donaldson Whyte. This edition included many revisions, but its new title was the most obvious change. To pay homage to the woman who had created the book, it was retitled Nellie Lyle Pattinson’s Canadian Cook Book.11

The second edition reflected the changing times. Suggestions for good nutrition were still included, but they now referenced Canada’s Food Rules, a guide implemented by the Canadian Council on Nutrition in 1944.12 The Rules reflected the practice of nutrition in Canada in the 1950s, which placed more emphasis on the consumption of dairy products than does the current edition of Canada’s Food Guide, revised in 2019.13 Added to the inside of the book jacket was a new table of weights and measurements.

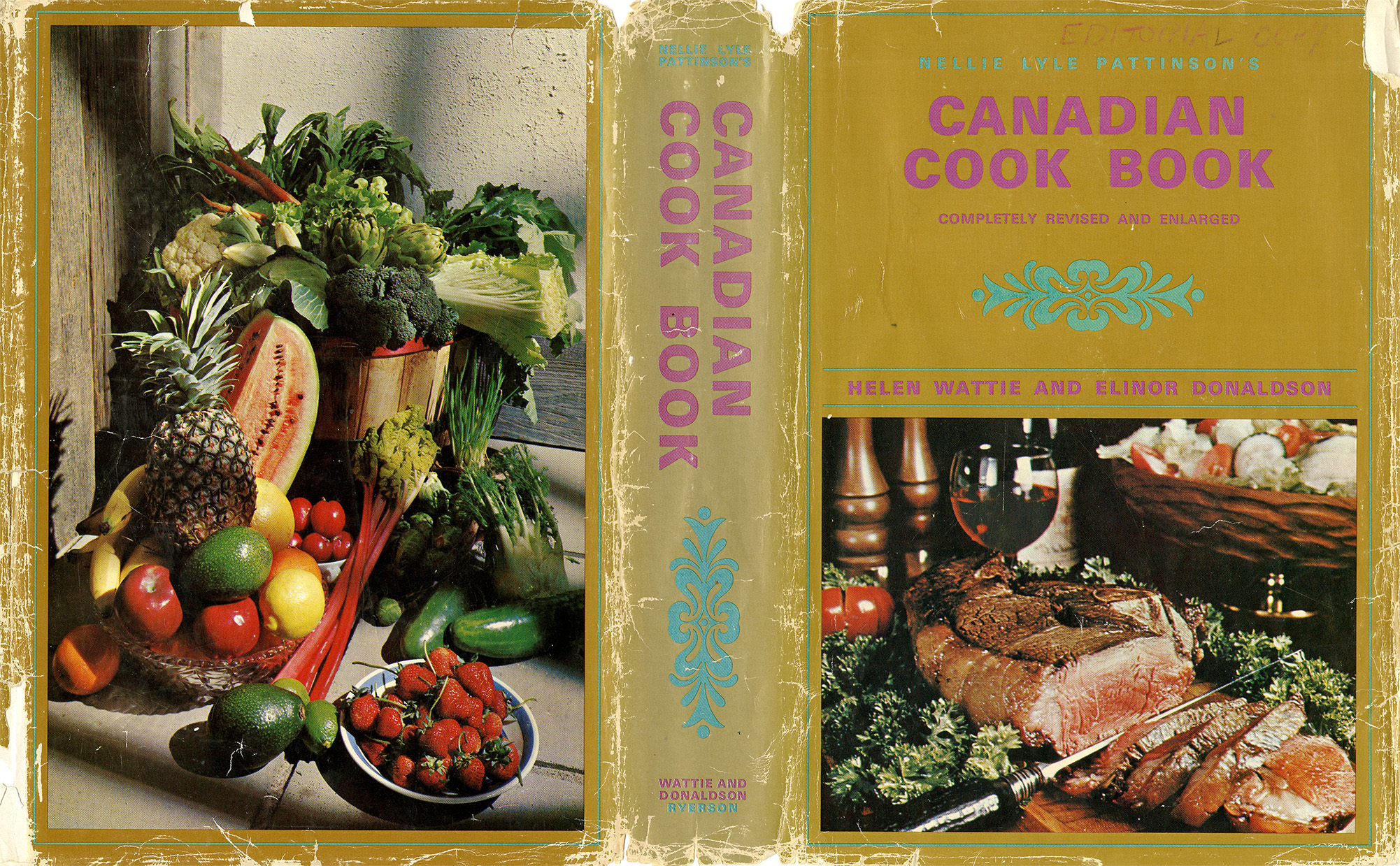

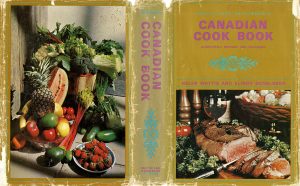

By 1969, it was time for another update to the Canadian Cook Book. Wattie and Donaldson Whyte remained editors for the third edition, which featured the tag line Completely Revised and Enlarged.15 The third edition, priced at $8.95 and now dressed in “a colourful jacket,” sold 12,137 copies between August 1969 and November 1970.16 It included more photographs than the previous editions, now with added colour due to the emergence of colour printing. It also referenced common can sizes, replacement values, and instructions for cooking techniques. This edition still offered nutritional information, but shifted its emphasis from healthy eating to eating regimens that altered health and body composition. The diet section in Planning and Serving Meals advised that dieting without medical advice was “foolish and risky,” but provided recommendations for cutting 500 calories from one’s diet for weight loss, and for adding 500 calories for weight gain.17 This section also provided information about specific diet plans – low cholesterol, low fat, and low sodium diets – diabetic meals, and working around allergies. An abbreviated chapter on meals for the sick was retained.

One of the most notable changes to the third edition was the integration of recipes for regional dishes into the regular chapters. An index, which listed the titles of recipes by region, referred readers to the chapter where each recipe could be found. This new format reflected Canada’s increasingly multicultural population and its attendant interest in diverse foods.

The Canadian Cook Book continued to be issued after McGraw-Hill acquired Ryerson Press in 1970.18 In 1979, it was still Toronto’s third best-selling cookbook and the first best-selling cookbook originating in Canada.19 By the 1990s, however, as Donaldson Whyte recognized, an increase in specialty cookbooks, packaged quick mixes, and take-out meals caused the Canadian Cook Book to lose its relevance20 and it was discontinued. Though publication ceased, the Canadian Cook Book remained a family favourite and continued to be passed down through generations.

In 2016, archivist Lorne Bruce described the Canadian Cook Book: “It was Canada’s first mass-produced cookbook, emphasized nutrition, [reflected] the pre-World War I development of household science economics courses, which combined arranging menus, home administration, budgeting, finance, and efficiency with cooking and serving, and … the postwar liberation of women through related workplace positions. Using ‘Canadian’ was inspired, tying it to Canada’s growing independence from England.”21 In 2018, the London-based publishing company, Forgotten Books, released a reprint of the Canadian Cook Book, noting the work’s historical significance.22

Although the Canadian Cook Book has faded from view, it remains an important part of Canada’s history. Its first creator Nellie Lyle Pattinson, and her successors Helen Wattie and Elinor Donaldson Whyte, stood for the advancement of women’s education and liberation through employment. By bringing nutritional information and modern innovation into the family home, they also helped establish a distinctive Canadian culinary culture. Their showcasing of regional recipes served to further broaden that culture, which sought to distinguish itself from British culinary tradition and practices.

The Canadian Cook Book remained in print for over sixty-five years, during which time it was a bestseller and personal favourite of families across Canada. That the book’s financial success also helped sustain the Ryerson Press was a testament to Lorne Pierce, the great mind behind the project. Today, the Canadian Cook Book remains a historical document for all and a family heirloom for many. Over the course of its long history, its several editions traced a developing culinary sensibility in Canada, provided insight into an emerging multicultural society, and presented a wide range of classic and regional recipes that were always tasty.

1 Susan Goldenberg, “Cooking with Nellie,” Canada’s History 13 December 2016.

https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/arts,-culture-society/cooking-with-nellie. This article first appeared in The Beaver (now Canada’s History) in October-November 2005.

2 Goldenberg.

3 Goldenberg.

4 Julie Van Rosendaal, “In Search of Canada’s First Cookbooks,” Globe and Mail 30 June 2018.

5 Elizabeth Driver, Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks 1825-1949, Studies in Book and Print Culture (Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2008) 616.

6 Nellie Lyle Pattinson, Canadian Cook Book (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1923).

7 “Voices of Our Past, Looking to Our Future: The Women of Kirkland Lake.”

http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/sgc-cms/histoires_de_chez_nous-community_stories/pm_v2.php?id=story_line&lg=English&fl=0&ex=00000836&sl=9632&pos=1.

8 Goldenberg.

9 Helen Wattie, Home Management and Nutrition (Toronto: General Publishing, 1968).

10 Clive Powell, “The Canadian Cook Book,” mychangingtimes 19 July 2016.

11 Goldenberg.

12 Helen Wattie and Elinor Donaldson Whyte, Nellie Lyle Pattinson’s Canadian Cook Book (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1953).

13 Canada’s Food Guide, 2019. https://food-guide.canada.ca/en.

14 Wattie and Whyte 1953.

15 Helen Wattie and Elinor Donaldson Whyte, Nellie Lyle Pattinson’s Canadian Cook Book (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1969).

16 Canadian Cook Book, by Helen Wattie and Elinor Donaldson Whyte, Production Card, September 1969, McGraw-Hill Ryerson Press Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Ryerson University.

17 Wattie and Whyte 1969.

18 Goldenberg.

19 Goldenberg.

20 Elinor Donaldson Whyte quoted in Goldenberg.

21 Lorne Bruce quoted in Goldenberg.

22 Nellie Lyle Pattinson, Canadian Cook Book (London: Forgotten Books, 2018).