Tucked away in Ryerson University’s Archives and Special Collections is a bulky, dark green cloth-covered volume with a gold embossed title that reads Types of Canadian Women and of Women Who Are or Have Been Connected with Canada, Vol. I. Written by Henry James Morgan and published in 1903 under the William Briggs imprint, the book is an impressive collection of more than 350 biographical sketches of Canadian women, spanning three centuries.1 Types of Canadian Women was conceived and published as the first of two volumes, but a second volume was never issued.

Born in Quebec on 14 November 1982, Henry James Morgan was a civil servant, author, and editor who published widely.2 Morgan saw a need to bolster the Canadian identity, which he strived to do through his many publications. He used his platform as a writer to simultaneously promote Canadian politics and culture, as well as the individuals who helped in the country’s development.3

The established and well-connected Morgan had many influential friends and contacts he often called upon for favours, which he repaid by including them in his biographical publications.4 Sketches of Celebrated Canadians (1862), for example, featured prominent figures from across Canada. After 1862, Morgan went on to develop a methodical system for his biographical work by basing his writing on responses to printed questionnaires.5 These he used in preparing the sketches of elected and appointed officials included in The Canadian Parliamentary Companion, a serial he edited from 1862 to 1876.6 He also produced Bibliotheca Canadensis (1867), which provides a comprehensive bibliography of “literary, historical, and political writings from 1763 to 1867” and remains an important resource for the study of Canadian literature.7

Modelled after Morgan’s other publications, Types of Canadian Women is traditional in approach, encyclopedic in scope, and lexical in format. The book differs, however, in its focus. For the first time, Morgan dedicates an entire volume to the histories and biographies of women and claims that “The Types in this work … represent three centuries and many marked contrasts of fashion and convention. They are of every class, from royalty to that of the bourgeoisie and the ranks of industry.”8 Despite his high-minded statement, Morgan does not showcase the diversity of Canadian women. In fact, rather than feature a wide range of women, Morgan’s biographical sketches conform to his overarching vision of life’s progress: “man is born; goes to college; obtains a degree; enters a profession or business; is elected to parliament; is called to office; performs certain acts of administration; is elevated to the bench; marries; and so forth.”9 Moreover, in the process of cataloguing female achievement, Morgan emphasizes the “man” in each woman’s life. His sketches often reflect at length on the successes of husbands, many of whom Morgan knew personally.

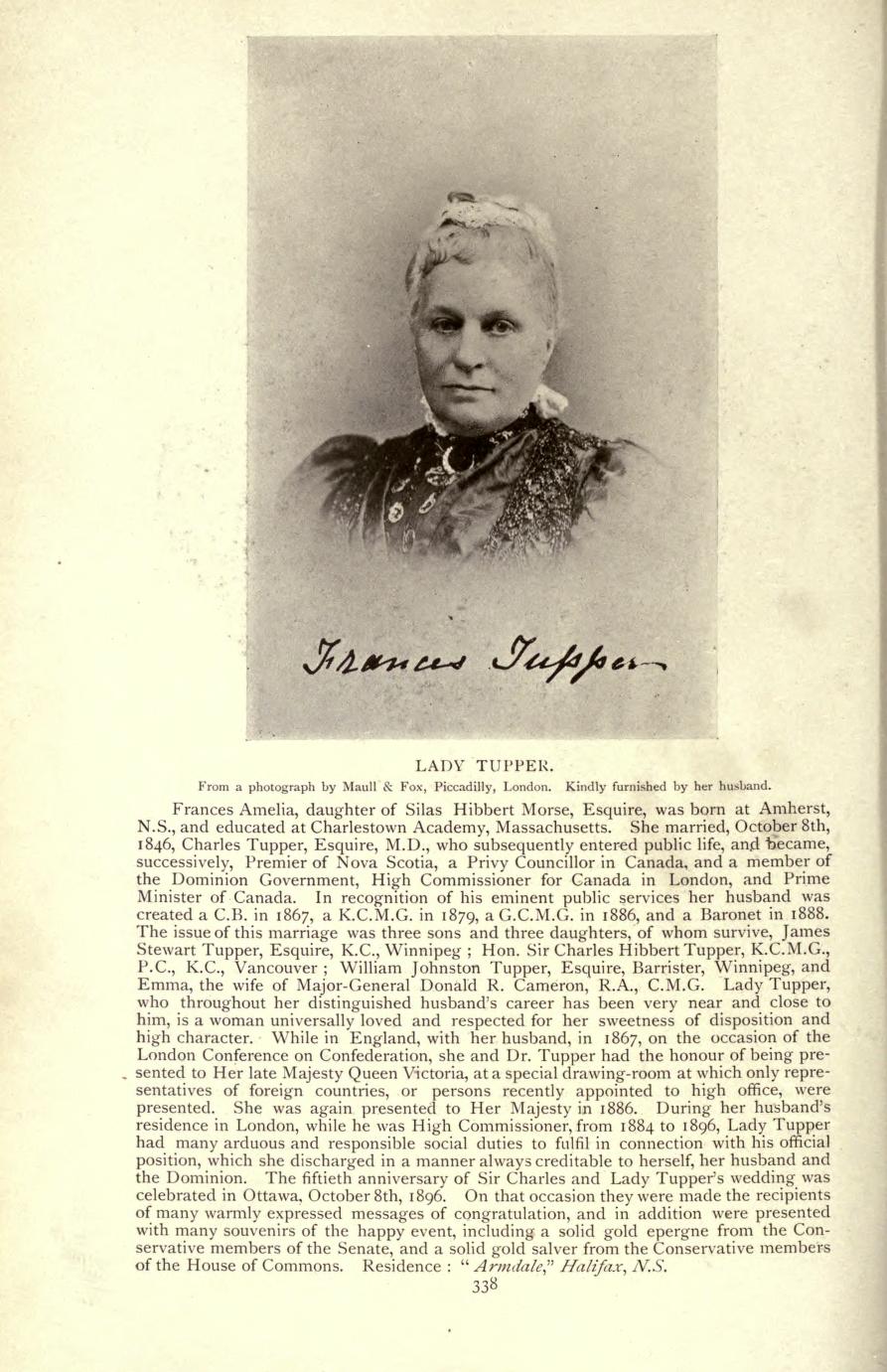

The biographical sketches in Types of Canadian Women are arranged alphabetically. Each sketch is accompanied by a photograph and identifies its subject by her married name. Often included is the woman’s date of birth and marriage, as well as a description of her husband and his accomplishments, their children, and her membership in societies and organizations. Overall, the sketches celebrate women’s primary roles as dutiful wife and mother and active community member.

Throughout the volume, Morgan tends to write deferentially about women who were married to influential men and who dedicated themselves to family, such as Lady Frances Amelia Tupper,10 the wife of Sir Charles Tupper, who was premier of Nova Scotia and later prime minister of Canada.11 Although Morgan credits Lady Tupper with no notable achievements of her own, he writes that she was “a woman universally loved and respected for her sweetness of disposition and high character” and details the esteem with which she carried herself in various social settings.12 Morgan does not probe the complexities of Lady Tupper’s public role as wife of so prominent a politician; rather, he shows respect for her status and admiration for her character.

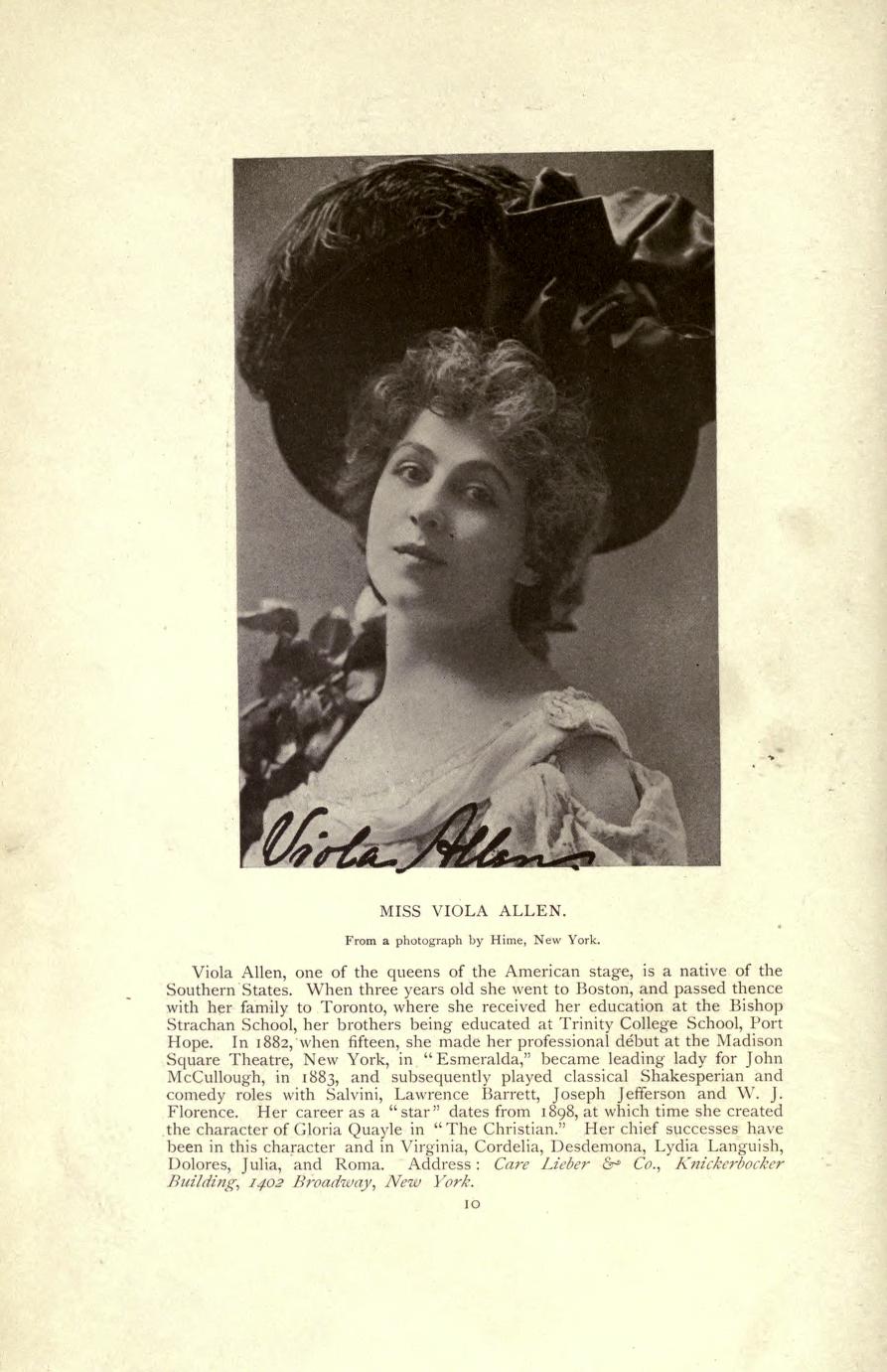

The majority of women Morgan features are white, upper-middle class, and married, those who prioritized traditional (i.e., heteronormative) family life. He also writes warmly, however, of women who were unmarried and forged successful careers in the arts – a fairly forward-thinking approach for the time.

Morgan writes with great enthusiasm, for example, about Miss Viola Allen and Miss Margaret Anglin, two actresses he features side by side. Morgan sings their praises, calling Allen “one of the queens of the American stage,13 and notes that in one of Anglin’s performances of 1898 “she gave evidence that she was in every sense an experienced actress, with a great future before her.”14 In the absence of a husband, Morgan concentrates on each woman and devotes a lengthy and detailed paragraph to her successful acting career, in which he traces her achievements over time. Remarkably, Miss Julia Arthur,15 also an actress, is identified by her first and last names, while her married name – Mrs. Cheney – is provided in parentheses. Although he is named as her spouse, Morgan focuses neither on Arthur’s husband nor on her marital status. Instead, he dedicates the full-page sketch to Arthur’s artistic career.

Available reviews of Types of Canadian Women suggest that its reception was mixed. A short review in the Academy of Literature, published in October 1903, noted: “These portraits represent three centuries, and many marked contrasts of fashion and convention. Full of excellent photographic reproductions accompanied by careful notes.”16 This brief positive statement conveyed appreciation for Morgan’s efforts without taking issue with the volume’s content. More recently, however, Morgan’s biographer Robert Lanning assessed the book as a vanity publication whose focus on women was a thinly veiled attempt to highlight the achievements of their husbands.17

There is no question that Types of Canadian Women is a product of its time. Nonetheless, it provides a rare glimpse into the lives of women in Canada, recording many important milestones and achievements that otherwise may have been lost. For contemporary readers, the publication is exciting to peruse for its many familiar names: philanthropists Lillian Massey, of the Massey manufacturers of agricultural equipment, and Grace Redpath, of Redpath Sugar fame; war heroine Laura Secord; and author Catharine Parr Traill.18 True, Morgan draws attention to the men in women’s lives. At the same time, however, he conveys respect for married women’s contributions to family life and single women’s career achievements alike, suggesting that value can be found in either path. His attitude was a progressive one for anyone – male or female – writing at the turn of the twentieth century.

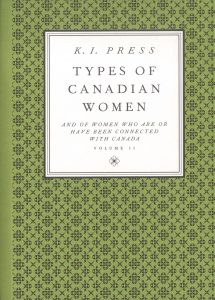

Recently, Morgan’s volume inspired the creation of Types of Canadian Women and of Women Who Are or Have Been Connected with Canada, Volume II, a collection of poems by K.I. Press published in 2006 by Nova Scotia’s Gaspereau Press. Just over a century after Morgan’s publication, Press presents her collection as the promised, but never published, second volume of Types of Canadian Women. Photographs of women appear alongside poems that explore various themes, such as gender roles, sexuality, rape and sexual assault, and women’s independence. While the women in the collection are rarely named, and remain purposely ambiguous figures, Press offers a nuanced and feminist perspective on what it means to be a Canadian woman and artfully bridges past and present concerns. Importantly, Press uses poetry for volume two of Types of Canadian Women; her response to Morgan’s work is through art, a medium that he himself praised highly.

Press portrays women as bold, unafraid, and assertive. A photograph of a young woman with downcast eyes wearing a floor-length dress and standing in front of a large flowering bush accompanies “Played Ingénues,” a poem composed of four stanzas. The speaker, ostensibly the woman in the photograph, critiques social convention by satirizing traditional expectations for women: “I do not eat. I have no unmentionable not to mention. I / do nothing I could not do in public. (Except sometimes the / gardener, in the willow trees.)”19 She takes pleasure in observing the men around her and does not hide her carnal desires, simultaneously recognizing the effect that she has on her suitors, as “men constantly / take off their hats, put them on, take them off, put them / on.”20

In the final stanza of “Played Ingénues,” the speaker asserts her power by speaking of the money she will earn. Having learned from her father who “likes to buy,” she follows his example and claims the same, typically masculine, privilege for herself. She lists the ways she will indulge herself, ending with the purchase of large men, so she can be “quiet and naughty.”21 Here, the female speaker takes charge of her sexual experiences, acknowledges her own worth, and determines to support herself; she does not need a man to thrive.

The final poem in Press’s collection, “Quick, Clever, Energetic and Good-Looking: A Typical Canadian Woman,”22 refers to the biographical sketch of Barbara Washington, one of the last women featured in Morgan’s Types of Canadian Women. The Canadian-born Washington23 (née Gibb) was a nurse, although little else is written about her beyond her extensive travels with her husband. The bulk of Morgan’s sketch is dedicated to honouring Washington’s husband, William Lewis Washington Jr., who served in the American Civil War and claimed to be a great-grandnephew of George Washington, first president of the United States. The final line, however, describes Barbara Washington “as a typical Canadian woman, quick, clever, energetic and good looking.” In contrast, Press’s Washington “cannot nod my head or hang it down: hair / nailed back, lips sewn shut, eyes propped open. Frozen. / Perpetual.”24 Press uses the final poem in her collection to link back to Morgan’s work and to comment darkly on the sketches in Types of Canadian Women, Vol. I, which she implies failed to explore the most meaningful facets of what it meant to be a Canadian woman at the turn of the twentieth century.

In 1903, Morgan sought recognition for Canadian women. That his book remains an important historical document is confirmed by Press, whose 2006 Types of Canadian Women, Volume II responds to the resonances in Morgan’s sketches and give his work new life through her poems.

1 Henry James Morgan, Types of Canadian Women and of Women Who Are or Have Been Connected with Canada, Vol. I (Toronto: William Briggs, 1903) vii.

2 Robert Lanning, “Morgan, Henry James,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, 1998. Accessed 16 August 2019, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morgan_henry_james_14E.html.

3 Lanning.

4 Lanning.

5 Lanning.

6 Lanning.

7 Lanning.

8 Morgan vii.

9 Lanning.

10 Morgan 338.

11 Morgan 338.

12 Morgan 338.

13 Morgan 10.

14 Morgan 11.

15 Morgan 13.

16 Review of Types of Canadian Women and of Women Who Are or Have Been Connected with Canada, Vol. I, by Henry James Morgan, Academy of Literature (1903): 442.

17 Lanning.

18 See the sketches of each woman in Henry James Morgan, Types of Canadian Women and of Women Who Are or Have Been Connected with Canada, Vol. I (Toronto: William Briggs, 1903) 335, 279, 309, 334.

19 K.I. Press, Types of Canadian Women and of Women Who Are or Have Been Connected with Canada, Volume II (Kentville, Nova Scotia: Gaspereau Press, 2006) 29, 1-3.

20 Press 29, 5-7.

21 Press 29, 11-13.

22 Press 113.

23 Morgan 348.

24 Press 113, 3-5.