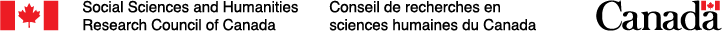

Emily Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) (1861-1913) was a writer of Mohawk and English origin born on the Six Nations reserve outside Brantford, Ontario. Johnson’s father, George Henry Martin Johnson, was Mohawk, which made Johnson native by birth, and her mother, Emily Susanna Howells, was English.1 Johnson saw herself as “primarily ‘Indian,’” but she recognized Canada as her home.2 Her Mohawk name, Tekahionwake, which she adopted from her great-grandfather (known also as Jacob Johnson),3 means Double Wampum and signifies Johnson’s bi-cultural identity.4

Johnson was best known as a poet and a performer whose work explored her dual Mohawk-English identity. The dramatic structure of her performances – at once distinctive and elaborate – showcased her hybrid identity. She presented her poetry clothed in a “trademark costume” of “native dress for the first half of her program and a drawing-room gown for the second [half].”5 Her performances were wildly popular and brought Johnson great fame. She became “one of North America’s most notable entertainers of the late 19th century.”6

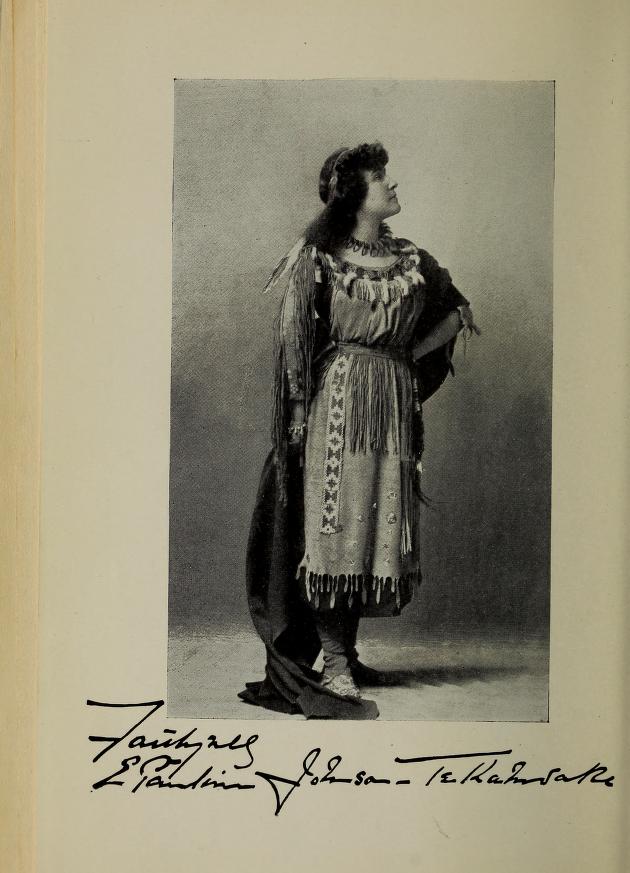

The stories in The Moccasin Maker, like Johnson’s verse, offer evocative and nuanced responses to her particular cultural inheritance. Issued posthumously under the William Briggs imprint in 1913, the year of Johnson’s death, The Moccasin Maker is an important work by an Indigenous writer published during Briggs’s stewardship of the Methodist Book and Publishing House. The volume brings together one essay and eleven short stories, all of which were issued during Johnson’s lifetime; seven of the stories first appeared in Mother’s Magazine, published out of Illinois.7

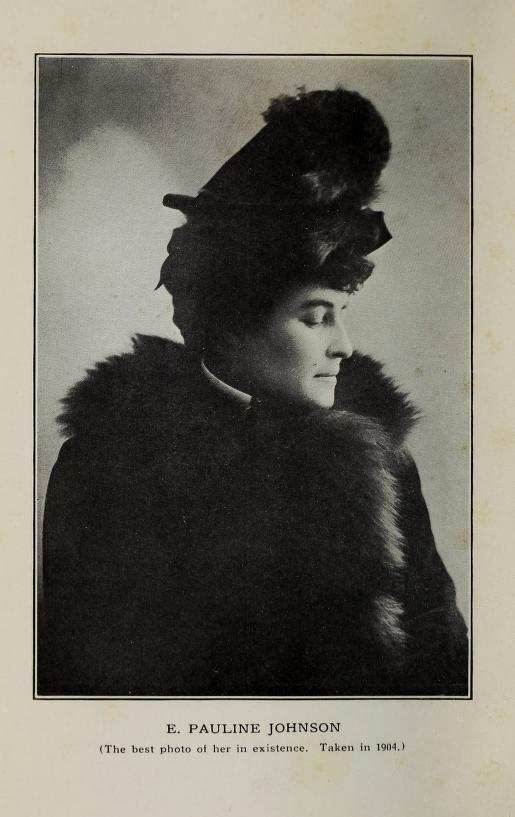

One version of The Moccasin Maker is bound in dark green ribbed cloth. On the front cover, the title appears in stylized black letters. A photograph, which serves as frontispiece, shows Johnson wearing an extravagant fur headpiece and lavish fur coat, with a caption that reads “The best photo of her in existence. Taken in 1904.”8 The meaning is unambiguous. Although the stories reflect Johnson’s experience as an Indigenous woman growing up and living in Canada, it is her whiteness that The Moccasin Maker finally emphasizes and validates.

Novelist Gilbert Parker’s introduction to The Moccasin Maker also underscores Johnson’s whiteness. Parker asserts, for example, that though she “was insistently and determinedly Indian to the end,” Johnson “had white blood in her veins.”9 He regards her work as “sure and sincere,” praises her technique as “good” and her “handling of narrative” as “notable,”10 and admits that The Moccasin Maker as a whole “makes one feel that Canadian literature would have been poorer, that something would have been missed from this story of Indian life if this volume had not been written.”11 At the same time, he denigrates Johnson’s collection for having “no striking individuality,” which “might have been expected from her Indian origin.”12

An “appreciation” of Johnson by poet Charles Mair follows Parker’s introduction and describes the impact she had on readers by bringing the experiences of Indigenous communities to light through the written word. While Mair claims to admire Johnson’s craft, particularly as a poet, his more general appraisal of what he identifies as “the Indian character” — which dominates the piece — shows an obvious lack of understanding of the true nature of colonialism and the devastating effect of colonization on Indigenous peoples and their lands.

Today, we perceive the prejudicial attitudes and patronizing assessments that characterize these responses to Johnson. In fact, the short stories in The Moccasin Maker refute any suggestion of their artistic inferiority and signal Johnson’s refusal to be defined by whiteness alone. Moreover, their very publication affirms the value of Indigenous culture and the possibility of successfully negotiating a complex dual identity. If anything should be taken from Parker’s introduction and Mair’s “appreciation” – ironically, both are included to lend weight and authority to the volume – it is an invitation to critically rethink outdated and inaccurate beliefs and instead continue to create space for Indigenous writers in the Canadian literary canon.

The power of The Moccasin Maker lies in Johnson’s ability to address core issues facing Indigenous peoples in Canada. Johnson uses her short stories to illustrate the difficulties of navigating a hybrid identity. She focuses particularly on explorations of love – platonic, familial, and romantic – and the challenges facing inter-racial/cultural couples. Johnson grasps the inevitable adversity facing such couples, including backlash from their respective communities. The first and longest story, “My Mother,” is written in four parts and spans Johnson’s mother’s lifetime. Here, the author examines her parents’ relationship, but she also addresses the Christianization of Indigenous children, the availability of alcohol and its effect on Indigenous communities, and recurring conflicts with settlers, themes that extend across the collection. “My Mother” also conveys Johnson’s deep love for her Mohawk culture and traditions, which lies at the heart of The Moccasin Maker.

What little record exists of its contemporary reception suggests that The Moccasin Maker was well received. In Toronto’s Globe of 6 December 1913, The Moccasin Maker is listed among the Season’s Best Books for Review and is described as “The story of the author’s mother’s life and other sketches and essays of Canadian life.”13 This brief notice broadens the cultural understanding of national identity by implying that Indigenous ways of life are distinctly Canadian.

Since its initial publication in 1913, The Moccasin Maker has remained in circulation and has seen new editions. In 1987, A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff, professor of English at the University of Illinois at Chicago, published a first scholarly edition of the work with the University of Arizona Press.14 The edition included an introduction, annotations, and a bibliography. In 1998, Ruoff’s scholarly edition was reissued by the University of Oklahoma Press.

Cecily Devereux’s 2001 review of The Moccasin Maker notes no major differences between the 1987 edition and the 1998 reissue.15 At the same time, she provides insightful analysis of the gaps in Ruoff’s annotations and interpretation of Johnson’s work. Devereux also addresses two key omissions. The first is Ruoff’s dismissal of Johnson’s hybridity and lack of nuance in unpacking the “constructed boundaries of race, nation, and empire” that shaped Johnson’s identity and informed both her writing and her live performances.16 The second is the exclusion of the introduction by Gilbert Parker and the “appreciation” by Charles Mair. Since the views of Parker and Mair evoke the cultural milieu of the time, and speak to prevailing attitudes toward women and Indigenous writers in early twentieth-century Canada, omitting this prefatory material effectively serves as an erasure of history.

Today, as Carole Gerson commented in 2012, Johnson is seen largely as a figure of resistance.17 In her day, however, Gerson argues that Johnson’s appeal to her largely Euro-Canadian audience was the result of “indigenization,” a term coined by Terry Goldie to describe the process of making Indigenous history palatable and accessible to a white audience comprised of immigrants and the descendants of immigrants to Canada.18 While it may be possible to read The Moccasin Maker as a sanitized work written to satisfy the contemporary taste for a more acceptable – and therefore less truthful – representation of Indigenous history in Canada, it is best understood as a work that seeks to offer a faithful and sensitive probing of what it means to balance a complex dual Mohawk-English identity.

Over the course of her career, Johnson used her platform as a prominent writer and popular performer to bring Indigenous culture and customs to mainstream audiences. Today, more than one hundred years after her death, her determination to raise awareness about Indigenous peoples and to foster appreciation for their traditions are all the more relevant, and the stories in The Moccasin Maker remain timely. As its recent appearance in scholarly dress would indicate, The Moccasin Maker will no doubt continue to be read and reinterpreted over time.

1 Marilyn J. Rose, “Johnson, Emily Pauline,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14. Accessed 7 October 2019, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/johnson_emily_pauline_14E.html.

2 Rose.

3 Rose.

4 Robinson.

5 Rose.

6 Amanda Robinson, “Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake),” Canadian Encyclopedia. Accessed 7 October 2019, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/pauline-johnson.

7 Betty Keller, Pauline Johnson: First Aboriginal Voice of Canada (Montreal: XYZ Publishing, 1999) 135.

8 E. Pauline Johnson, The Moccasin Maker (Toronto: William Briggs, 1913).

9 Gilbert Parker, Introduction, in The Moccasin Maker, by E. Pauline Johnson (Toronto: William Briggs, 1913) 5.

10 Parker 5.

11 Parker 7.

12 Parker 5.

13 “The Season’s Best Books in Review,” Globe [Toronto] 6 December 1913: 10.

14 Cecily Devereux, “EPJ in ‘New’ Reprint,” review of The Moccasin Maker, by E. Pauline Johnson, ed. A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff, Canadian Literature 168 (Spring 2001): 162. See A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff, ed., The Moccasin Maker, by E. Pauline Johnson (Tuscon: U of Arizona P, 1987) and A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff, ed., The Moccasin Maker, by E. Pauline Johnson (Norman, OK: U of Oklahoma P, 1998).

15 Devereux 163.

16 Devereux 162-63.

17 See Carole Gerson, “Rereading Pauline Johnson,” Journal of Canadian Studies 46.2 (Spring 2012): 45-61.

18 Gerson 46. See also Veronica Strong-Boag and Carole Gerson, Paddling Her Own Canoe: The Times and Texts of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), Studies in Gender and History (Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2000) and Carole Gerson and Veronica Strong-Boag, eds., E. Pauline Johnson, Tekahionwake: Collected Poems and Selected Prose (Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2002).