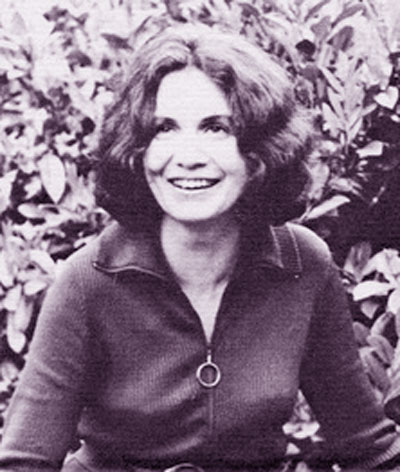

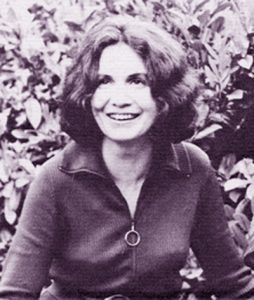

Alice Munro (born 1931) is one of Canada’s most accomplished and renowned writers, recognized for popularizing and canonizing the short story. Munro explores themes of womanhood, aging, and everyday life in stories rooted in place and time, and in a distinctive style that has come to be known as Southern Ontario Gothic. Over the course of her career, Munro has won more than twenty literary prizes, the first of which was the Governor General’s Literary Award for Dance of the Happy Shades, her first collection of short stories published by Ryerson Press in 1968.

Alice Munro (née Laidlaw) was born and raised in the town of Wingham in southwestern Ontario. In 1949, she received a two-year scholarship to attend the University of Western Ontario (now Western University), where she studied English literature and journalism. In 1951, when her scholarship ran out, she left university and married fellow student James Munro. At the time, having completed the first two years of an undergraduate degree, Munro was more educated than most women. Later, Alice and James Munro moved to Vancouver; in 1963, they relocated to Victoria, where they established Munro’s Books, the long-thriving bookstore.1

As an undergraduate student, Munro published several stories in Folio, the University of Western Ontario’s creative writing magazine. Ambition led her to submit stories to the New Yorker, but when her early work met with rejection she decided to focus instead on the Canadian market. In the 1950s, she succeeded in publishing stories in journals such as Canadian Forum and Tamarack Review. She later formed a close relationship with the New Yorker, which now claims her as “our Chekhov.”2

In his foreword to the first edition of Dance of the Happy Shades, although he described Munro as a “literary artist,”3 novelist Hugh Garner felt compelled to justify the short story as a valid form of literature. In fact, Garner’s foreword paid more attention to literary mentor Robert Weaver than to Munro herself. Weaver had joined the CBC as a program organizer in 1948 and immediately had begun to solicit work by Canadians, which aired regularly on radio programs such as Canadian Short Stories (1946-1954), CBC Wednesday Night (1947-1963), Critically Speaking (1948-1967), and later Anthology (1954-1985) and Stories with John Drainie (1959-1965). In Garner’s view, Weaver transformed the CBC into one of the best markets for “a good short story.”4

Soon after she left university, Munro began a correspondence with Weaver. She also sent him stories that he broadcast on Anthology and published in the Tamarack Review – Weaver was an editor of the journal. A strong advocate, Weaver entrusted himself with the task of sending Munro’s stories to publisher Jack McClelland of the publishing house McClelland and Stewart. In a letter to Munro dated 24 August 1961, Weaver announced that McClelland was “at least interested in publishing perhaps half a dozen of the stories.”5 In the same letter, Weaver reassured Munro: if all else fails, there was a possibility of issuing a book through the Tamarack Review.6 One of the ironies of Munro’s early literary career is that she benefitted from the assistance of prominent male figures – first Weaver, then Garner – to help promote her writing, which focused on womanhood, marriage, and the complex lives of female protagonists.

On 22 November 1961, soon after he had submitted her work to McClelland and Stewart, Weaver wrote to Munro with good news: “Ryerson Press want to see … five short stories since they are trying to find some work by younger writers.”7 Weaver took it upon himself to send Munro’s “stories to a friend of mine at Ryerson Press.”8 Despite the expression of interest, however, an unexplained and protracted delay ensued, and it was not until 1967 that editor Earle Toppings invited Munro to assemble a collection of stories for book publication.9 Finally, in September 1968, Dance of the Happy Shades was published.

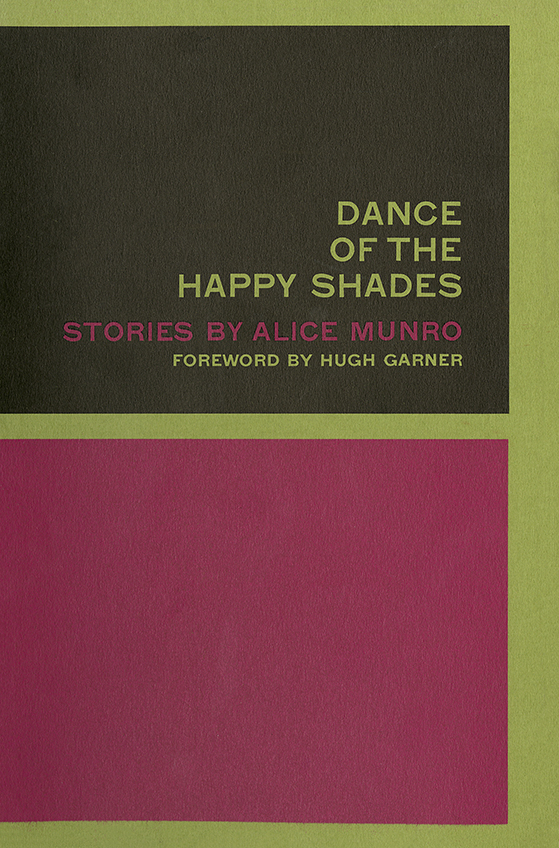

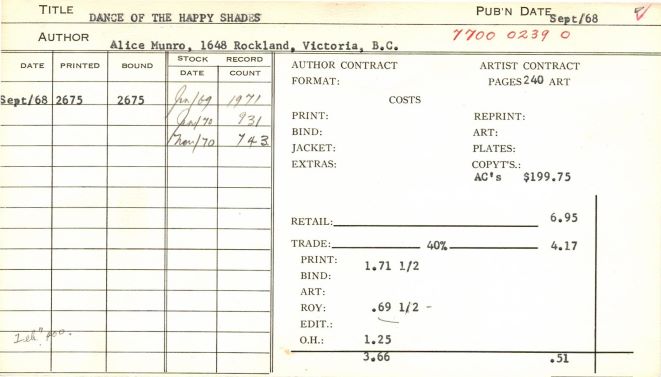

The volume’s simple design belied the explosive significance of its content. The front cover of the dust jacket consisted of an olive green border and line across the centre, which divided the cover into two sections. The upper portion was black, while the lower portion was fuchsia. Over top of the black background, the title appeared in olive green and the subtitle, Stories by Alice Munro, appeared in fuchsia. A blurb by Weaver, which lauded Munro as one of the few “authentic and stubbornly persevering writers who have kept the short story alive” in Canada, appeared on the back cover. The first printing of Dance of the Happy Shades consisted of 2675 copies. By November 1970, 1932 copies had sold for a retail price of $6.95.10

The stories in Dance of the Happy Shades, which use the mundane to veil the dark and complex themes of womanhood, aging, and death, were written over a span of fifteen years. “The Day of the Butterfly,” for example – originally published in Chatelaine under the title “Goodbye Myra” – was written when Munro was twenty-one. “Images,” the last story she wrote for Dance of the Happy Shades, tackled the themes of fear, maturation into adulthood, and death. To do so, Munro wrote through the mind of a child whose fragmented understanding of the world is transformed by her wilderness experiences with her father. Munro indirectly incorporates the idea of a child learning about danger, as she perceives the potential for violence in the wilderness. Across the collection, universal ideas are grounded in the realism of life in rural southern Ontario. As she revealed in a 2015 interview, early on Munro was drawn to writing about life in small town settings because “the small town is like a stage for human lives.”11

Upon its release, Dance of the Happy Shades garnered favourable reviews. A brief notice in Chatelaine, for example, listed Dance of the Happy Shades as recommended reading for November 1968. The review noted Munro’s “skill and sensitivity that will evoke many memories in Canadian readers.”12 In the Globe and Mail, Sheila Fischman praised Munro’s homage to rural Canada and the book’s unique “sensibility touched with humour, not unaware of the absurd.”13 Fischman went on to say that Dance of the Happy Shades achieved a difficult task in making “common experiences … unique but universal expressions … of what it means to be alive.”14 She also commended Ryerson Press for publishing a short story collection by a lesser-known writer. Overall, Munro’s first collection was met with effusive praise from reviewers and readers alike.

After she received the Governor General’s Literary Award for Dance of the Happy Shades – Weaver, her long-time mentor, was head of the selection jury – Munro reflected on the difficulties of reaching an audience: “You see a lot of things in a bookshop. For instance, customers are always impressed with a thick book. They also convince me that short stories are poor sellers because, they explain, they want something they can get into.”15 As the co-owner of Munro’s Books, the author had first-hand knowledge of readers’ tastes. As a writer, however, she did not bow to readers’ preference for “thick” books, i.e., novels. Instead, she persisted in crafting short stories that would go on to win her an international audience, as well as great acclaim. She received the Governor’s General Literary Award again in 1978 and 1986 for Who Do You Think You Are? and The Progress of Love, respectively;16 the Giller Prize (now the Scotiabank Giller Prize) in 1998 and 2004 for The Love a Good Woman and Runaway, respectively;17 and the Man Booker International Prize in 2009, in recognition of her body of work.18

Ryerson Press, in issuing her first award-winning collection, gave Munro the confidence and determination to pursue her writerly interest in the short story. For launching Munro’s remarkable career, which culminated in 2013 when she received the Nobel Prize in Literature,19 Ryerson Press deserves its own recognition for seeing promise in Munro’s work and for being the first publisher to bring her stories to the public.

1 See Aida Edemariam, “Alice Munro: Riches of a Double Life,” Guardian 4 October 2003. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/oct/04/featuresreviews.guardianreview8.

2 James Wood, “Alice Munro, Our Chekhov,” New Yorker 10 October 2013.

3 Hugh Garner, Foreword, in Dance of the Happy Shades, by Alice Munro (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1968) viii. See also Karis Shearer, “‘Now back to your stories’: Framing the First Canadian Edition of Alice Munro’s Dance of the Happy Shades,” Caliban 53 (2015): 195-200.

4 Garner.

5 Robert Weaver to Alice Munro, 24 August 1961, MsC37.2.8.4, Alice Munro fonds, Archives and Special Collections, University of Calgary.

6 Robert Weaver to Alice Munro, 24 August 1961, MsC37.2.8.4, Alice Munro fonds.

7 Robert Weaver to Alice Munro, 22 November 1961, MsC37.2.8.8, Alice Munro fonds, Archives and Special Collections, University of Calgary.

8 Robert Weaver to Alice Munro, 22 November 1961, MsC37.2.8.8, Alice Munro fonds.

9 Catherine Sheldrick Ross quoted in JoAnn McCaig, Reading in Alice Munro’s Archives ([Waterloo]: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2002) 53.

10 Production card, Dance of the Happy Shades, by Alice Munro, September 1968, 7700 0239 0, McGraw-Hill Ryerson Press Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Ryerson University Library.

11 “Person 2 Person: Alice Munro,” TVOntario, 21 July 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TlXjN6rnGb4.

12 “Books,” Chatelaine (November 1968): 10.

13 Sheila Fischman, “To Maturity along a Rural Route,” Review of Dance of the Happy Shades, by Alice Munro, Globe and Mail 19 October 1968: A24.

14 Fischman.

15 Munro quoted in Jo Carson, “Governor-General’s Award Winner: Writer Meditates Way across Generation Gap to Prize,” Globe and Mail 21 May 1969.

16 McCaig 59.

17 https://scotiabankgillerprize.ca/finalists/.

18 https://themanbookerprize.com/international.

19 Julie Bosman, “Alice Munro, Storyteller, Wins Nobel in Literature,” New York Times 10 October 2013: A3.