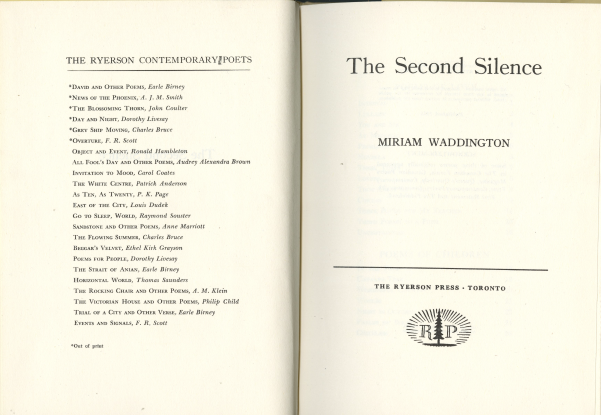

Ryerson Press helped launch the career of Miriam Waddington (née Dworkin) (1917-2004), who is regarded today as one of Canada’s groundbreaking modernist poets. In the 1950s, Ryerson published two volumes of Waddington’s socially conscious verse, The Second Silence (1955) and The Season’s Lovers (1958) — in editions of 500 copies each — setting the stage for a career that spanned the latter half of the twentieth century.

Waddington was born in Winnipeg to Russian Jewish immigrants. Her parents were secular Jews “deeply involved in the vivid intellectual life of Winnipeg’s Russian Jewish community,”1 which was concentrated in the city’s North End, a vibrant enclave of Jewish, Polish, and Ukrainian immigrants and one-time centre of Jewish life in the West. Today, Winnipeg’s North End enjoys the same legendary status as St. Urbain Street in Montreal, immortalized in large part by novelist Mordecai Richler as the former Jewish heart of that city. The Dworkins may not have attended synagogue, but their circle of friends and acquaintances included Jewish and Yiddish writers and poets, lecturers, musicians, and actors, some of whom were Zionists, socialists, and anarchists.2

The language spoken at home was Yiddish and Waddington absorbed its familiar tone and “conversational directness,”3 qualities that would come to characterize her own verse in English. She learned the value of Yiddish from her parents who signaled its cultural significance: “My parents made a conscious effort that we should speak only Yiddish at home, because they felt like many secular Jews that a language was a culture … a spiritual home … and since they were not religious they perhaps transferred their religious feelings to the language and literature and to the Yiddish culture.”4

Waddington’s formative years were characterized by tension between her inner and outer lives. She recalled that her “inner life, my really freer life was the one I had in the Jewish parochial school,”5 the I.L. Peretz Folk School, which she attended until grade four. In 1927, she left the liberal atmosphere of the socialist-oriented parochial school and transferred to a public school. Much “more authoritative”6 than the Peretz Folk School, Machray School served students from diverse cultural backgrounds. Students were of Jewish, Polish, Galician, English, and Scottish heritage and the majority of the teachers were of Scottish origin. Although Waddington had fond memories of her teachers — they “were very nice, [and] I think they had a strong moral sense”7 — her fellow students were less congenial. During her years at Machray, she regularly heard the racist slur “dirty Jew.”8 She quickly learned that “it wasn’t good to be Jewish, but … it was really good to be English.”9 As a result, she developed ambivalent feelings for her Yiddish-speaking parents and their friends. Her ambivalence ran deep: “The injustice of being excluded from certain things because I was Jewish often embittered my life.”10

It was as a grade six student at Machray School, however, that Waddington first tried her hand at poetry. Poetry soon became her “refuge”11 and the “act of writing that relocates the inner feelings and outer experience”12 became a source of pleasure, too.

In 1930, Waddington’s family moved to Ottawa, where she attended Lisgar Collegiate Institute. Six years later, she entered the University of Toronto. She earned a BA in English in 1939 and a diploma in social work in 1942, and for the next two years was a case worker with Jewish Family and Child. In 1944, Waddington enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Social Work as a Master’s student and was a case worker with the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic while she studied toward her degree.

Waddington once described herself as a “divided person … I have this side of me that is practical, that is realist, rational and is interested in ideas. And I have a social side and … an individual side. I feel guilty, if I don’t do something in a societal way.”13 Although she completed an undergraduate degree in English, Waddington chose a career in social work. Her firm belief in social responsibility and community — that to “love humanity takes courage, daring, and faith”14 and that “one should [not] be too individual”15 — drove her altruism. Her rational side, however, responded to the theories of psychoanalyst Otto Rank, who argued for a balance between “creative and cognitive processes” and believed that the artist unconsciously “searches out and finds … the experiences he needs for his art.”16 Rank’s view that the artistic impulse is an attempt to reconcile individual and collective tendencies held great meaning for Waddington.

Waddington’s experience at the University of Pennsylvania was “liberating, painful, and growth-producing”17 and had a lasting effect on her life and work. In fact, her earliest verse was concerned explicitly with the social conditions of urban life and invoked the experiences of actual individuals she had counseled. As she recalled, in “poetry the relation between myself and the client somehow became closer and more intimate, and I could not help writing many poems about my experiences in child-guidance clinics, adoption and family agencies, hospitals, courts, and prisons.”18

Waddington earned an MSW in 1945 and that summer moved to Montreal with her husband, Patrick Waddington, who had accepted a job with the International Service of the CBC. Between 1945 and 1960, she pursued a career in social work, balancing part-time case worker positions and lecturing at McGill University’s School of Social Work while she raised her two sons, Marcus (born in 1946) and Jonathan (born in 1951). Although “the physiological and social demands of being mother, wife, and household manager dominated”19 her life, Waddington continued to write in the evenings. Her writerly ambitions were further roused when she joined Montreal’s vibrant literary community, which had formed in the early 1940s around John Sutherland, the writer, critic, and founder of the literary magazine First Statement and First Statement Press. In fact, Waddington once confessed to having “always been a poet, before I was anything else and more truly than I was anything else.”20

Waddington had hoped to place her first volume with Ryerson Press, but was twice rebuffed by Lorne Pierce in 1943 and 1945. As a result, First Statement Press, a small literary publisher, issued Waddington’s first book of poems, Green World, in 1945.21 It was, however, the more established and influential Ryerson Press, which published her next two books — The Second Silence in 1955 and The Season’s Lovers in 1958 — that eventually generated the critical attention Waddington deserved.

Waddington believed that content and form were inseparable and that each poem was an “organic” structure with “its own existence and integrity … part of a particular time, place, and person.”22 Her approach to the act of writing was often intellectual, but her verse was never cerebral and her language was consistently “transparent and simple so that it could say something that others would recognize and respond to.”23 Her poetic persona — the outsider who is allied with the marginalized and feels sympathy for the vulnerable — and lyric voice — direct, questioning, often troubled — were distinguishing features of her verse. In addition, attention to poetic form regularly lent her work a playful, open quality.

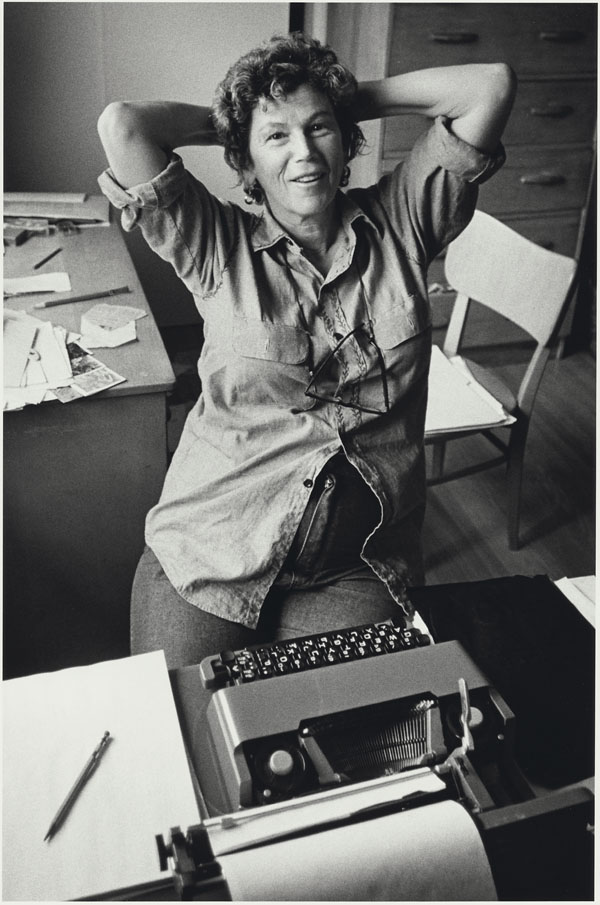

Although she often resisted “getting started … once I do … I write and scratch out a lot … I start out with an image or a line, one thing leads to another, and then I have a rough draft.”24 It was Waddington’s practice “to write the whole poem out in a sketchy form; and then if I have two or three unbroken days, I work on that same poem for maybe four or five hours a day … I revise and revise and revise while I’m working on a poem … the essence of writing is in the revisions.”25 Initial drafts were composed by hand and then revised on a typewriter; Waddington never used a computer. When she did not “have time to finish a poem, and I usually don’t, I put it away. Though I always plan to, I seldom go back to a poem after several weeks or months. As a result I have many folders of unfinished poems.”26 Waddington mourned these unfinished efforts as “orphan” poems.

Waddington was always a voracious reader of verse and her two collections of the 1950s issued by Ryerson deployed traditional poetic conventions — formal stanzaic structure, long lines, and “occasional flamboyant language”27 — the marked influence of Dylan Thomas and W.B. Yeats, whose work she knew and admired. Initially, she aimed for “formality, measure, lucidity, spaciousness, and proportion”28 in her poetry. Peter Stevens, in his 1985 profile of Waddington, notes that she read the English poets of the 1930s, and critic L.R. Ricou has traced her poetic affinity with the American writer Theodore Roethke.29

Among Jewish contemporaries, Waddington’s compassionate humanism aligned more closely with the reflective and literate tenor of A.M. Klein’s verse than the flamboyant and rousing quality of Irving Layton’s poems, and the intimate tone of much Yiddish poetry. Waddington, like Klein and Layton, gradually turned away from conventional verse forms in favour of modernist experimentation, but her perspective as a secular Jew differentiated her poetry from that of the more traditional Klein and her sentience diverged from the hyper-masculinist ethos embraced by Layton.

Waddington’s earliest verse received a mixed reception from the coterie of critics who reviewed her work. A critical bias against Waddington’s poetry was especially evident in the 1940s and 1950s, a period of intense self-scrutiny among Canadian critics who sought to articulate a modernist literary practice that excluded much writing by women. Like their British and American counterparts, Canadian modernist critics — the majority of whom were male — valued “an implicitly masculine aesthetic of hard, abstract, learned verse that is opposed to the aesthetic of soft, effusive, personal verse supposedly written by women.”30 Critic Carole Gerson identifies “the critical canon-forming decades between the wars” as favouring women’s writing that conformed “to a Romantic/sentimental/domestic model.”31 Such writing was easily dismissed by male critics, as were attempts by female authors to engage “with modernist methods.”32 Hence, women writers were doubly disadvantaged, but Waddington was determined to leave her mark as a socially engaged poet with a focus on the quotidian and she continued to write.

Northrop Frye and Eli Mandel were two prominent critics who offered balanced assessments of Waddington’s first publications. For Frye, The Second Silence revealed Waddington’s “own distinctive quality: a gentle intimacy and an unmediated, though by no means naïve, contact between herself and her world.”33 He singled out “Morning until Night” as a poem of striking originality, which turns on an irresolvable conflict of identity: “Two crows have I harboured long in me, / Because I love doves I imprisoned crows, / Forced them to silence; at night they wakened me / With constant clamour.” Frye later observed that the poet’s “two gifts, one for spontaneous lyricism and one for precise observation” were “better integrated”34 in The Season’s Lovers.

Mandel — who was himself a poet — observed that Waddington was an accomplished urban poet: “No one else knows [the city] … like she does or tolerates it so completely.”35 Mandel was moved particularly by “the stunning conclusion … horrifying in its ambiguities”36 to “My Lessons in the Jail”: “For moments in the hallway, compose your face / To false good humor, conceal your sex: / Smile at the brute who runs the place / And memorize the banner, Christus Rex.”

In 1986, Waddington claimed that “an artist shouldn’t exploit his/her personality. The work should speak for itself and the personality should remain in the background.”37 Although she struggled to divorce personality from artistic expression, life experience nonetheless informed Waddington’s verse, gave it its distinct shape and colour, dimension and depth — precisely those facets of her poetry that resonate still with today’s readers. The Ryerson Press must be credited with recognizing Waddington’s artistry and encouraging her poetic development. Moreover, in publishing the work of Waddington and other Jewish poets — A.M. Klein, Norman Levine, and Eli Mandel, for example38 — Ryerson Press, whose roots lay in the Methodist Church, showed a striking openness and commitment to showcasing Canada’s diversity.

1 Albert Moritz, “Profile: From a Far Star,” Books in Canada (May 1982): 5.

2 Moritz 5.

3 Peter Stevens, “Miriam Waddington,” in Canadian Writers and Their Works. Poetry Series, Volume 5, ed. Robert Lecker, Jack David, and Ellen Quigley (Toronto: ECW Press, 1985) 279.

4 Wolfgang Binder, “An Interview with Miriam Waddington,” Commonwealth Essays and Studies 11.2 (1989): 83-94.

5 Binder 83.

6 Binder 83.

7 Binder 83.

8 Binder 84.

9 Binder 84.

10 Miriam Waddington, “Outsider: Growing Up in Canada,” in Apartment Seven: Essays Selected and New, by Waddington, Studies in Canadian Literature (Don Mills: Oxford UP, 1989) 40.

11 Binder 87.

12 Miriam Waddington, “Form and Ideology in Poetry,” in Apartment Seven: Essays Selected and New, by Waddington, Studies in Canadian Literature (Don Mills: Oxford UP, 1989), 159.

13 Binder 91.

14 MG31-D54, box 2, file 15, Miriam Waddington fonds, Library and Archives Canada.

15 Binder 90.

16 Waddington, “Form and Ideology in Poetry” 158.

17 Miriam Waddington, “Apartment Seven,” in Apartment Seven: Essays Selected and New, by Waddington, Studies in Canadian Literature (Don Mills: Oxford UP, 1989) 33.

18 Waddington, “Apartment Seven” 20.

19 Miriam Waddington, Afterword, in Collected Poems, by Waddington (Don Mills: Oxford UP, 1986) 412.

20 Waddington, “Apartment Seven” 19.

21 See Miriam Waddington, Green World (Montreal: First Statement Press, 1945).

22 Waddington, Afterword 411.

23 Waddington, Afterword 416.

24 Marvyne Jenoff, “Miriam Waddington: An Afternoon,” Waves 14.1-2 (Fall 1985): 5-6.

25 Jon Pearce, “Bridging the Inner and Outer: Miriam Waddington,” in Twelve Voices: Interviews with Canadian Poets, by Pearce (Ottawa: Borealis Press, 1980) 180.

26 Jenoff 6.

27 Stevens 282.

28 Waddington, “Form and Ideology in Poetry,” 162.

29 See Peter Stevens, “Miriam Waddington,” in Canadian Writers and Their Works. Poetry Series, Volume 5, ed. Robert Lecker, Jack David, and Ellen Quigley (Toronto: ECW Press, 1985) 277-329; and L.R. Ricou, “Into My Green World: The Poetry of Miriam Waddington,” Essays on Canadian Writing 12 (Fall 1978): 144-61.

30 Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Guber, No Man’s Land: The Place of the Woman Writer in the Twentieth Century (New Haven: Yale UP, 1988) 153-55.

31 Carole Gerson, “The Canon between the Wars: Field-notes of a Feminist Literary Archaeologist,” in Canadian Canons: Essays in Literary Value, ed. Robert Lecker (Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1991) 55.

32 Gerson 55.

33 Northrop Frye, “Letters in Canada: 1955. Poetry,” Review of The Second Silence, by Miriam Waddington, University of Toronto Quarterly 25 (April 1956): 297.

34 Northrop Frye, “Letters in Canada: 1958. Poetry,” Review of The Season’s Lovers, by Miriam Waddington, University of Toronto Quarterly 28 (July 1959): 357.

35 Eli Mandel, “Poetry Chronicle,” Review of The Season’s Lovers, by Miriam Waddington, Queen’s Quarterly 67 (Summer 1960): 292.

36 Mandel 291.

37 Jenoff 12.

38 See A.M. Klein, The Rocking Chair and Other Poems (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1948), Norman Levine, Myssium (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1948); and Eli Mandel, Blood and Secret Man (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1964).