Lorne Pierce, who may have preferred the excitement of building a list of significant trade titles, also grasped the importance of textbook publishing to Ryerson Press. He understood that textbook contracts would help establish a solid financial base for his firm and advance Ryerson’s reputation as an educational publisher. He knew, too, that textbook publishing would enhance Ryerson’s cultural influence and its profile as a national publisher. At a time when Canadians were asserting a taste for educational texts that evoked a sense of their place in an expanding and changing world, Pierce facilitated access to those books.

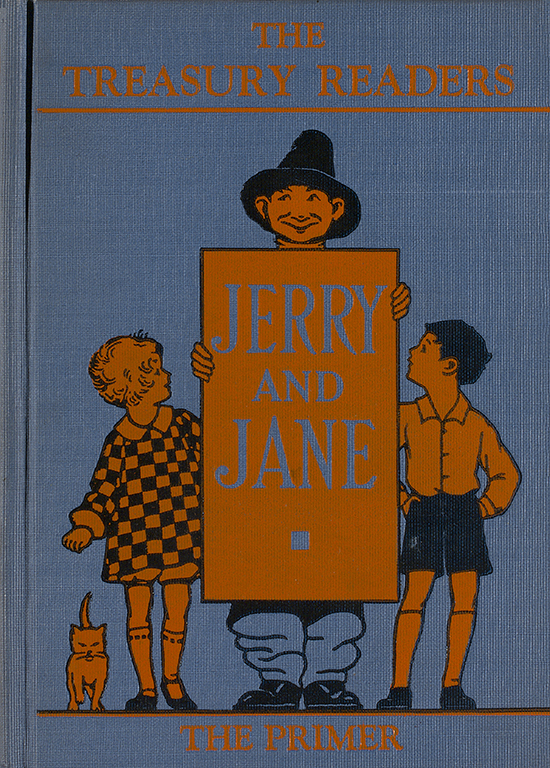

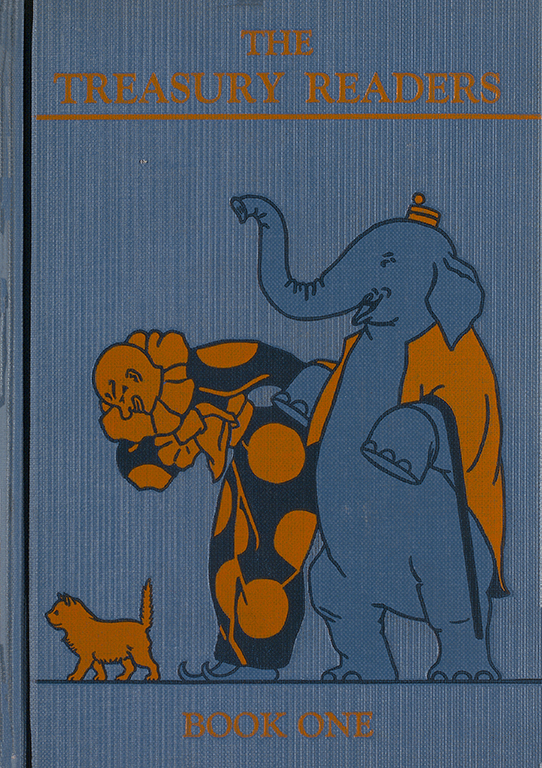

In 1929, when he proposed a collaboration between Ryerson Press and the Macmillan Company of Canada, Pierce could not have anticipated the triumph – and the frustration – that would come of this shared venture in textbook publishing. Of particular importance is the Treasury Readers, an educational series that was launched at the height of the Great Depression and developed during the 1930s. Throughout this period of economic turbulence and financial instability, Lorne Pierce and Hugh Eayrs – the president of Macmillan – were buoyed by their success as joint publishers of the Treasury Readers.

The series represented a rare instance of competitors collaborating in an attempt “to cut competition”1 in order to secure the remunerative textbook market. As Eayrs explained in a letter dated 27 September 1937 to Daniel Macmillan, his overseer in the London home office: “In response to a straight tip from the Interprovincial [Schoolbook] Committee [of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba] that no one house would get the [textbook] contract, we have associated with us the Ryerson Press … at once the most dangerous competitor and the best book manufacturer, a house like our own of substance and repute.”2 Eayrs, who was newer to publishing and head of a much younger firm (established in Toronto in 1905), admired Pierce for his knowledge and had great respect for Ryerson Press, at the time one of English Canada’s oldest and most highly regarded publishing companies.

Books one to three of the Treasury Readers series were originally published in the Canada Books of Prose and Verse series, under the editorship of Lorne Pierce of Ryerson Press. Although Pierce had conceived of the series in 1929, he and Eayrs signed a formal agreement in April 1932 to jointly edit and publish the newly named Treasury Readers series, a continuation of the Canada Books of Prose and Verse series. The new series, which had been in preparation throughout 1931, would comprise a primer and readers for grades one through eleven, together with manuals, workbooks, and supplementary teaching materials; books one to three were to be revised as readers for grades seven, eight, and nine. Pierce was named editor-in-chief of the series, while Eayrs was associate editor. Their aim was “to make this a Canadian series and to introduce an intelligent national note. Of course we shall be reasonable about it. Not all our poets are classics! Yet we feel that we can arouse sympathetic understanding of the singers of our country, and our prose writers as well … each student shall gain a progressive appreciation of the finer spirit of the Dominion.”3

The Treasury Readers series held great commercial promise for Ryerson and Macmillan. Eayrs anticipated “that these readers will be adopted as the authorized readers for the four Western Provinces. If we are right it will be much the biggest deal the House has ever had, and will involve an extra turnover of some $100,000 a year.”4

Eayrs was also confident in his alliance with Pierce, who was highly respected both as an intellectual and a publisher. Biographer Sandra Campbell claims that Pierce “was arguably Canada’s most influential publisher and editor in the period from Canada’s coming-of-age after the First World War to the Quiet Revolution [in Québec (1960-1966)].”5 Eayrs correctly assumed that his editor-in-chief lent credibility to their joint series, which he regarded as “perfectly architected [sic] … This is solely due to the sound scholarship and the awareness of modern pedagogical thinking which are part and parcel of Lorne Pierce. As the editor-in-chief of the Series you have in him a man with an essentially fine mind, concerned first of all with the beautiful and the lasting, and secondly with the up to date. I am satisfied that so far as the text is concerned no Series can match ours.”6

The honeymoon period was short-lived, however. Although Pierce and Eayrs continued to work alongside one another for many years, their personalities often clashed. The serious Pierce and flamboyant Eayrs were opposite in temperament and work habits. Pierce, a teetotaller, was dedicated and meticulous, “an academically inclined editor,”7 while Eayrs was bibulous and worked in great spurts of frenetic energy. That their business practices differed considerably was also a recurring source of conflict.

Dissension characterized the start of Ryerson and Macmillan’s partnership. In March 1932, Pierce claimed Eayrs was competing with their joint series when the latter submitted Macmillan’s St. Martin’s Classics series to the Ontario board of education for its consideration. Eayrs countered that he had “no right to prescribe” Pierce’s “general publishing policy, and you have no right to prescribe mine. Both of us intend to defend the one venture, a very large one, in which we are so very deeply interested.”8 Eayrs’s response served to allay Pierce’s concern, but only briefly. Their connection was punctuated by lapses in Pierce’s trust of Eayrs, whom he regularly suspected of disingenuous behaviour.

In practice, Eayrs struggled to mask duplicitous behaviour with natural charm. In July 1933, for example, he chose to holiday in Lake Louise, forty miles from Banff, Alberta, where the interprovincial schoolbook committee was meeting to assess textbook submissions. Surreptitiously, he arranged that Archibald Herriott, inspector of schools in Manitoba, “one of the committee people at Banff, which we can trust, should know that we are at [Lake] Louise, and therefore could get any word to us [i.e. Eayrs and Pierce] if it were necessary.”9 Eayrs’s plan worked to Macmillan and Ryerson’s advantage. When he learned from Herriott – who received five hundred dollars for being a staunch, if somewhat corrupt, ally – that the committee found the Treasury Readers series too highly priced, Eayrs and Pierce immediately reduced the cost of the readers. In the end, despite Eayrs’s determination and political connections, the schoolbook committee decided to split the textbook contracts between Ryerson-Macmillan and their rivals Gage-Nelson – another two Toronto book publishers that had joined forces in a highly competitive market. Nonetheless, Eayrs and Pierce were pleased by their qualified success and heartened by further interest in the Treasury Readers shown by the Nova Scotia boards of education.

The association between the two publishers was not always as happy. In June 1935, calamity ensued when Gage-Nelson accused Ryerson-Macmillan of plagiarism. John Gray, employed at the time in Macmillan’s education department, was conscripted to manage the crisis. When Gray was presented with the claim that the grade seven reader included more than fifty teachers’ notes culled from American textbooks – “chiefly an American Rand-McNally reader for which Gage-Nelson held Canadian copyright”10 – he was filled with apprehension. Ten thousand copies of the reader had already been printed and distributed in Alberta. Gray understood the legal ramifications facing Ryerson and Macmillan and was catalyzed into action. In a diplomatic coup that won the approval of all parties involved, Gray proposed that the grade seven reader be used for the year, that Gage-Nelson’s grade eight reader be adopted the following year, and finally, that Ryerson and Macmillan would eliminate the plagiarized passages in subsequent printings of the grade seven reader and grant Gage-Nelson access to copyrighted material. Previously Pierce and Eayrs had ruthlessly refused their competitors access to the work of authors whose copyright resided with either Ryerson or Macmillan and their respective agencies. Hence, the work of Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, W.B. Yeats, and many other prominent writers, for example, had appeared in Macmillan’s readers alone.

Gray was congratulated on his careful handling of a potentially incendiary situation and Pierce and Eayrs continued their collaboration, albeit much more carefully. As Campbell admits, however, “the whole episode was embarrassing for Ryerson-Macmillan, and especially [so] for Pierce,”11 since he may have been responsible for the plagiarized passages.

Until 1937, when the last title in the series appeared, Pierce and Eayrs sought to advance the Treasury Readers series. Over the years they kept abreast of the competition, expanded the market for the series, ensured the timely production of each reader, and maintained conciliatory negotiations. Pierce even edited two early books in the series with Eayrs’s wife, Dora Whitefield, who helped choose the illustrations for both volumes.

In fact, despite their contrasting styles, Pierce’s intellectual dedication and Eayrs’s dynamic creativity proved a winning combination. They had correctly judged the potential of educational series in general, and the Treasury Readers in particular, to generate substantial profits for Ryerson and Macmillan, broaden each company’s reach as an educational publisher, and influence generations of Canadian students. Over thirty-five years, notes Campbell, the “hugely successful readers, in a variety of titles and editions, became widely used texts in elementary schools and high schools in much of English Canada.”12 By 1961, the textbooks for grades seven to twelve sold 200,000 copies annually across Canada.13 The series was also instrumental in introducing students to many Canadian writers, including poets Bliss Carman, William Henry Drummond, Oliver Goldsmith, E. Pauline Johnson, Archibald Lampman, Wilson MacDonald, Marjorie Pickthall, Charles G.D. Roberts, and Duncan Campbell Scott, and prose writers Ralph Connor, Frederick Philip Grove, Stephen Leacock, Ernest Thompson Seton, and Catharine Parr Traill. As Campbell affirms, the series “were the first Canadian readers with systematic and extensive Canadian literary content, and they had an important role in fixing recognition of Canadian writing in the minds of elementary and high school students.”14

Textbook publication extended Ryerson’s reach into the formative settings of Canada’s primary and secondary schools. This formidable classroom presence solidified the firm’s reputation as one of Canada’s pre-eminent educational publishers, a reputation that would advance over the course of the twentieth century. Moreover, by securing a large share of the educational market, Pierce ensured his company’s financial stability, which underwrote other publishing ventures, in particular Ryerson’s trade programs, where his true passion lay.

1 Lorne Pierce to Hugh Eayrs, 25 March 1932, Macmillan Company of Canada fonds, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, McMaster University Library. Hereafter MCC fonds.

2 Hugh Eayrs to Daniel Macmillan, 27 September 1932, MCC fonds.

3 Lorne Pierce to P. H. Sheffield, 14 November 1930, MCC fonds.

4 Hugh Eayrs to Daniel Macmillan, 14 October 1931, MCC fonds.

5 Sandra Campbell, “Nationalism, Morality, and Gender: Lorne Pierce and the Canadian Literary Canon, 1920-60,” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 32.2 (Fall 1994): 135.

6 Hugh Eayrs to Frances Ormond, 15 January 1932, MCC fonds.

7 Campbell, “Nationalism, Morality, and Gender” 136.

8 Hugh Eayrs to Lorne Pierce, 20 May 1932, MCC fonds.

9 Hugh Eayrs to Lorne Pierce, 19 July 1933, MCC fonds.

10 Sandra Campbell, Both Hands: A Life of Lorne Pierce of Ryerson Press (Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2013) 309.

11 Campbell, Both Hands 311.

12 Campbell, “Nationalism, Morality, and Gender” 142.

13 John Webster Grant, Report of the Book Editor to the Board of Publication, April 1961, box 45, file 17, Lorne and Edith Pierce Collection, Queen’s University Archives.

14 Campbell, “Nationalism, Morality, and Gender” 142. See also chapter 6, “Textbooks: Campbell B. Hughes, 1947–1969,” in Ruth Bradley-St-Cyr’s “The Downfall of the Ryerson Press,” PhD dissertation, U of Ottawa, 2014, pp. 148-71.