The first accrual of the McGraw-Hill Ryerson Press Collection consists chiefly of some 3,000 books and pamphlets issued under the Ryerson Press and its predecessor imprints, bound collections of publisher’s catalogues, and some 1,800 contracts, mostly between publisher and author. A second accrual that I have been fortunate to examine – this accrual is currently being processed – includes bound collections of pamphlets comprising a complete run of the Ryerson Canadian History Readers, many of the Ryerson Essays, additional educational readers and trade books, and a number of unbound publisher’s catalogues from the late 1950s to 1968. The second accrual further includes about 75 cm of book production cards dating from the late 1930s to 1970. Approximately seventy photographs portraying Ryerson Press staff and operations and about one hundred author photographs from 1934 to 1960 are also part of the donation. Once processing is complete, the second accrual will become an invaluable resource for researchers. In fact, information derived from material held in both the first and second accruals of the McGraw-Hill Ryerson Press Collection informs several of the essays and case studies included in this exhibit. This case study describes a serendipitous discovery process using the archival tools at hand.

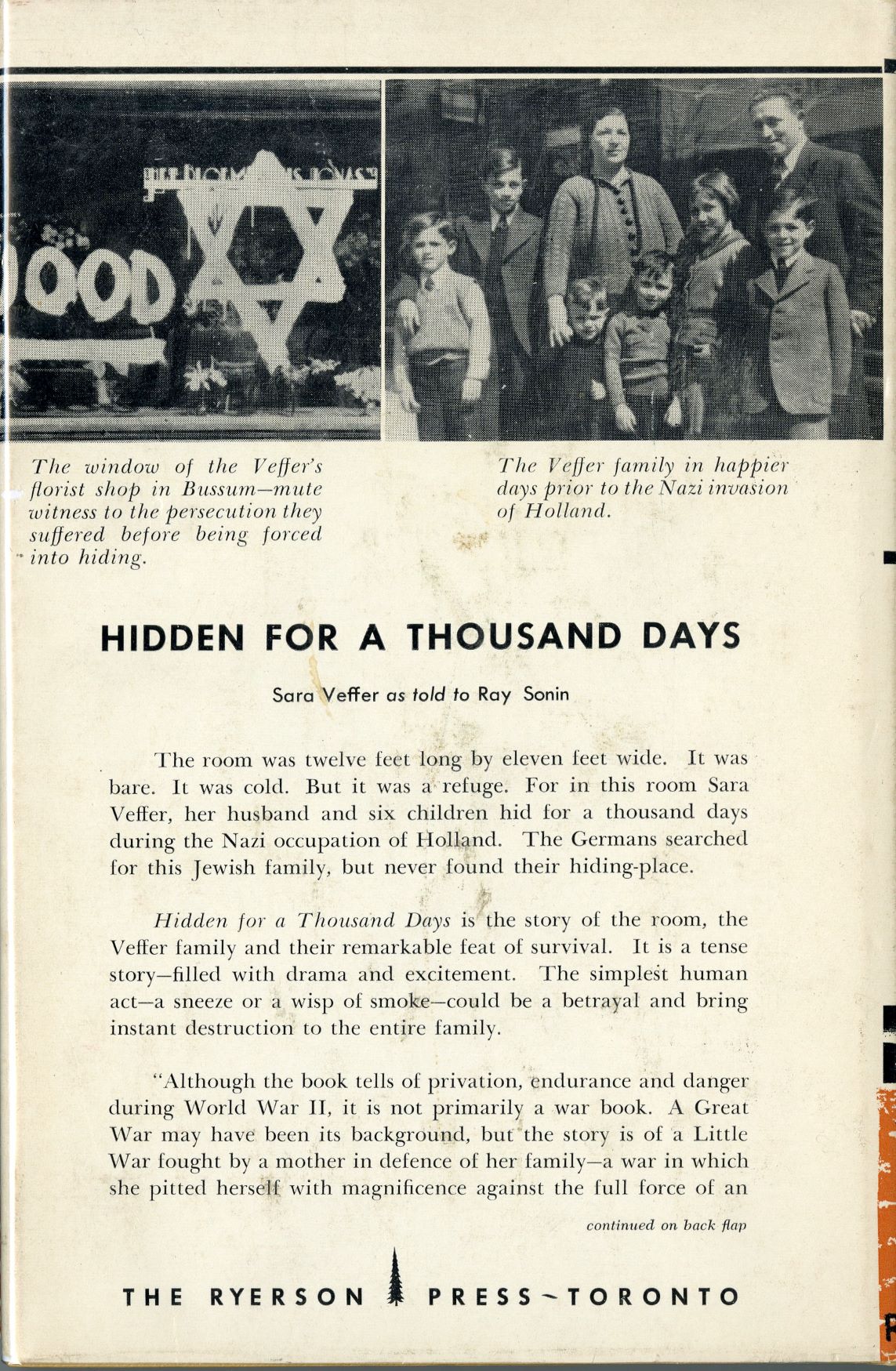

My discovery began with a photograph of a family featuring two adults and six children, which I found among the many author photographs included in the second accrual. Pencilled on the back of the photograph was a note: “Mrs. Veffer. Back of jacket ‘Hidden for a Thousand Days.’” A quick search of the inventory list of McGraw-Hill Ryerson books donated to the Ryerson University Library failed to identify the work. The University of Toronto and WorldCat catalogues revealed, however, that this image was associated with Hidden for a Thousand Days, a book written by Sara Veffer as told to Ray Sonin and published by Ryerson Press in 1960. From the catalogue entries, I gleaned that this was a Holocaust narrative about a Jewish family from the Netherlands. I assumed that the book likely represented an early example of a published Holocaust memoir. Further research confirmed this assumption.

Just as I discovered Veffer’s memoir, I was tasked with identifying a book for the Ryerson University Library that could be purchased to honour our Chief Librarian Emerita, Madeleine Lefebvre, on the occasion of her retirement. Immediately, I thought of Hidden for a Thousand Days. Thus, using the antiquarian book marketplace, I located and acquired a nice copy with a good dust jacket. The book would not only mark Lefebvre’s significant contributions as Ryerson University’s chief librarian from 2007 to 2017, it would also be an important addition to our library collection.

Even before I received the copy of Veffer’s memoir, I searched for a book review and found one in the Globe and Mail, dated 1 October 1960.1 From this review, I learned that Sara and Jonas Veffer and their children were residing in Toronto. In 1940, however, when the Nazis occupied Holland, they had been proprietors of a prosperous flower shop in Bussom, a town located approximately fifteen miles east of Amsterdam. As the situation for Jews deteriorated, the family went into hiding and lived for some 1,000 days in a 132 square foot room on the second floor of an inconspicuous house.

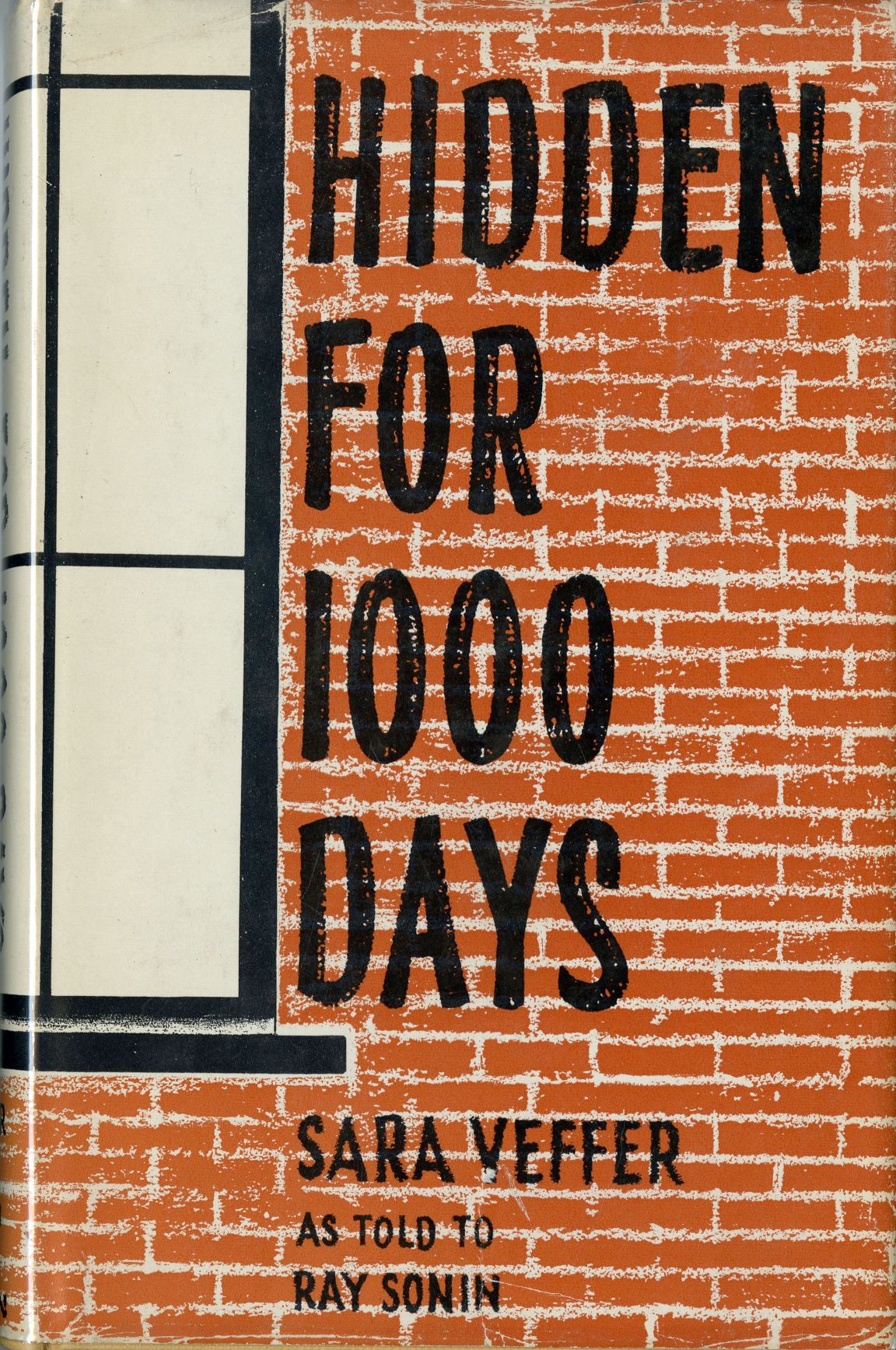

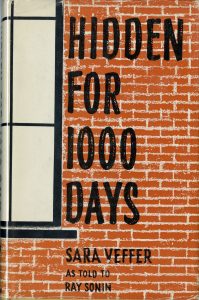

When the book finally arrived, I saw that the archival photograph I had uncovered – taken before the German occupation of the Netherlands and subsequent persecution of the country’s Jewish citizens – was reproduced on the back of its dust jacket. I admired the dust jacket, which had been designed for great effect. The unidentified artist, in choosing to display “thousand” as a number rather than a word, made a striking statement. A second alteration of the title on the dust jacket was the removal of the article “a” before the number “1000.” What was the intent? Perhaps it was meant to convey a language usage by someone whose native tongue was not English? The stylized title was set against a backdrop illustration of a brick wall, which contrasts with the windowpanes at the left that bleed over to the spine of the book. Here, the blank windows are meant to suggest that the glass has been papered or boarded over to hide whatever or whoever is inside from the free world on the street.

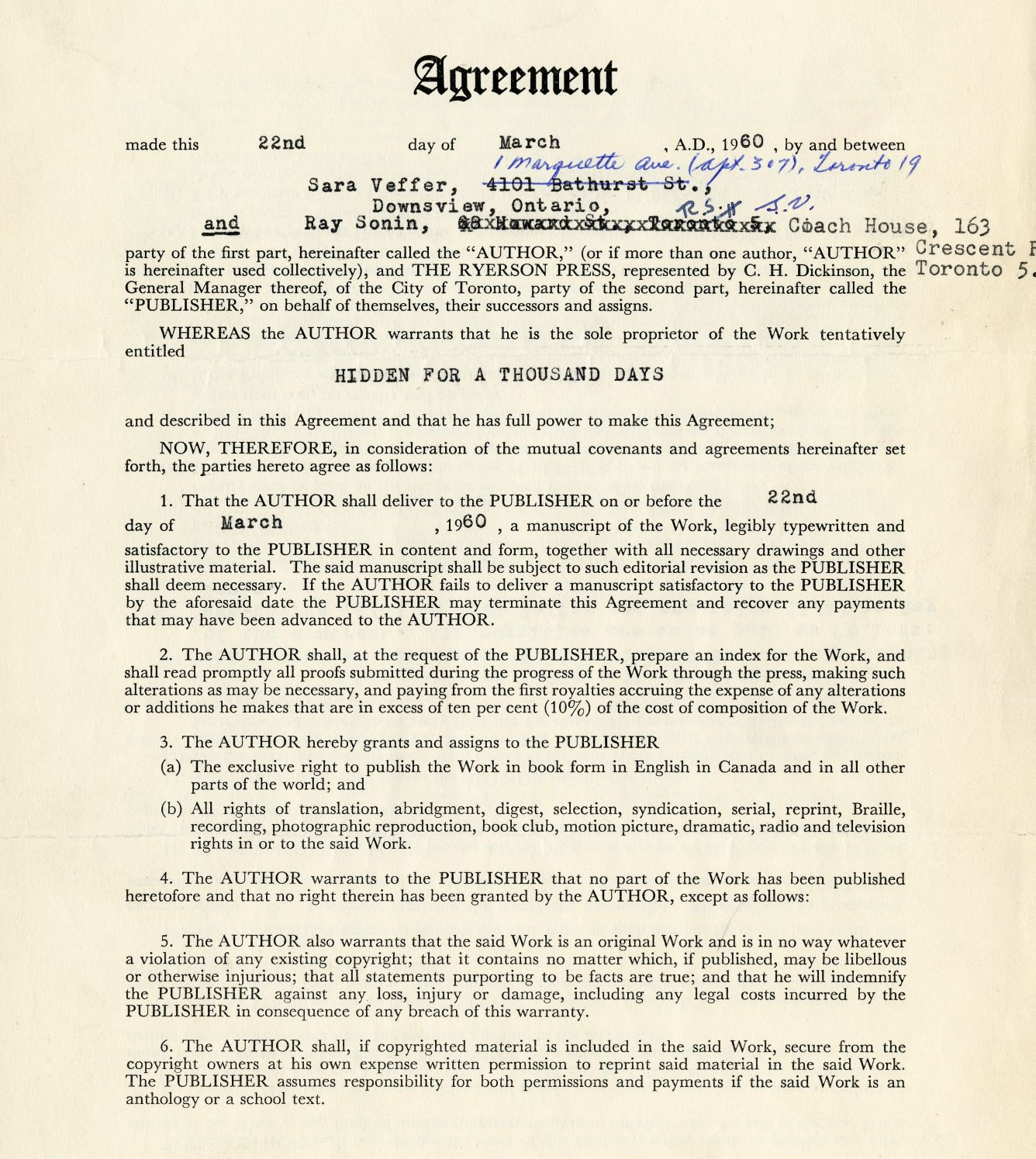

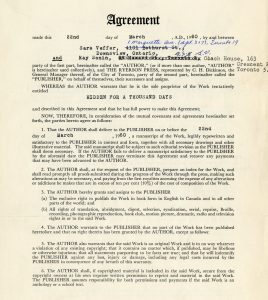

What else did I learn about this book by using the archival materials at hand? The publishing contract is extant, as identified in the finding aid: https://archives.library.ryerson.ca/index.php/veffer-sara-and-sonin-ray. Dated 22 March 1960, the agreement contains boilerplate language with some typed in details, such as a ten percent royalty payment to be shared by Sara Veffer (who was to receive two-thirds) and Ray Sonin (who was to receive one-third of royalties). Alongside the agreement are copies of supplemental correspondence. One letter, dated 18 July 1961, transferred to Veffer and Sonin the rights of translation into the Dutch language. (I have searched WorldCat, but can find no evidence that a Dutch translation was ever produced.) In another letter, dated 22 May 1964, Ryerson Press returned to Veffer and Sonin all rights, except book and subsidiary rights in English Canada. Finally, the file includes correspondence from January 1984, wherein McGraw-Hill Ryerson informs Max Veffer, Sara Veffer’s son: “Since the book is no longer in print, we no longer claim any rights to the work, and this letter will confirm that all rights have reverted to the author.”

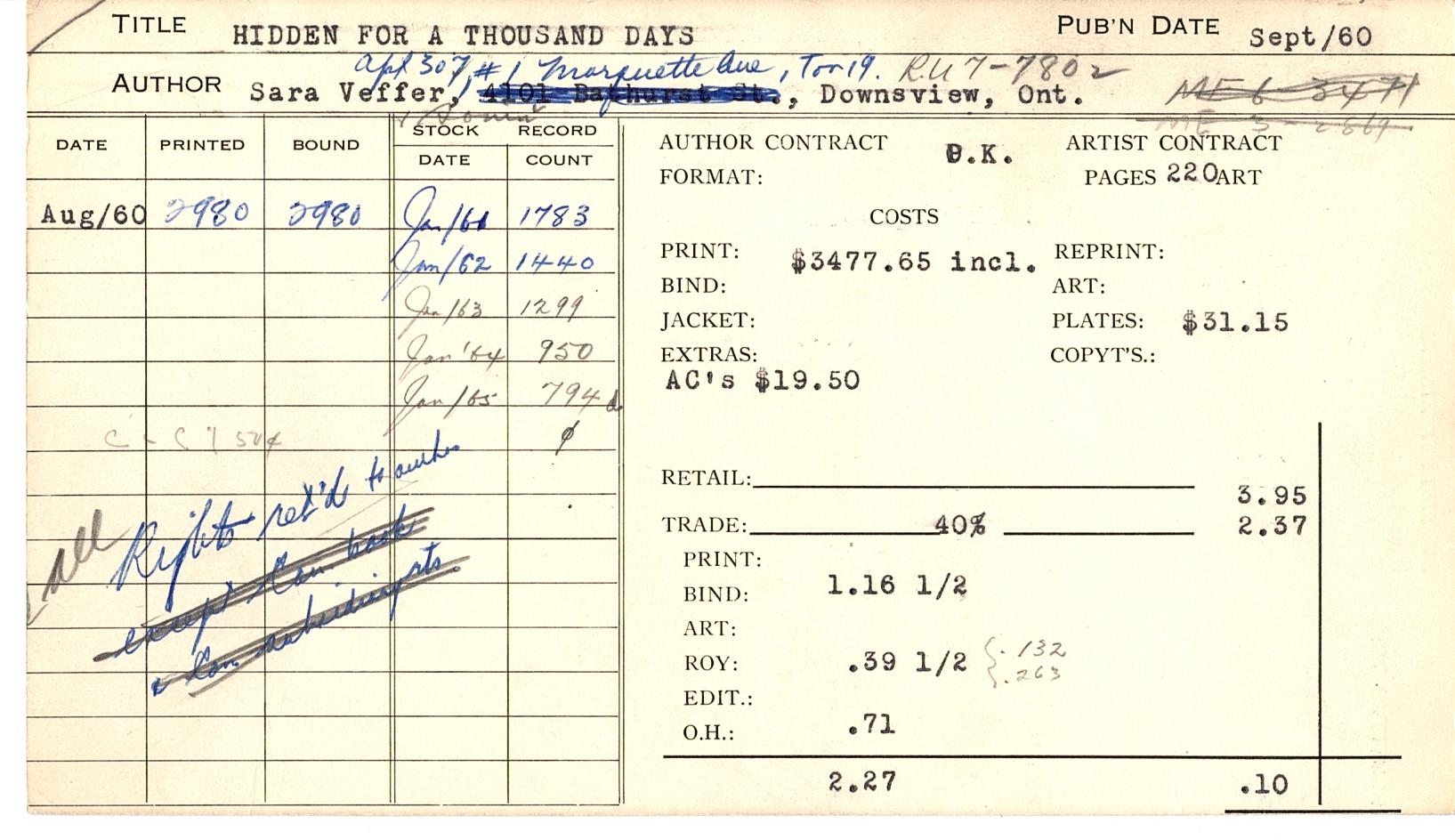

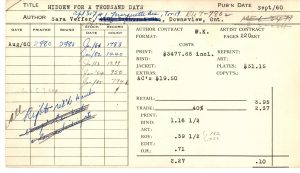

Also extant is a book production card. The production record is much richer than one might think upon first examination. In addition to providing identification, such as the title of the book, its date of publication (September 1960), and Sara Veffer’s name and current address, it shows the number of copies printed (2,980), the number of copies bound (also 2,980), and the number of books in stock at the time of inventory in January 1961 (1,783), January 1962 (1,440), January 1963 (1,299), January 1964 (950), and January 1965 (794). A final undated record count of zero suggests that at some point during 1965 all remaining stock was disposed of. A note indicates “all rights ret’d to author.” The card further records the following details: the fact that a publishing contract was on file; a page count; the costs associated with production and binding; and the book’s retail and trade prices. The slim profit margin was only ten cents on a book that retailed for $3.95 and wholesaled for $2.37. The recto of the card records eight subsidiary rights that Ryerson Press tried to obtain and the specific dates in 1961 when those attempts came to naught. Although the firm placed the title with an agent in California for a twelve-month period starting 7 March 1962, WorldCat records no other editions of Veffer’s book.

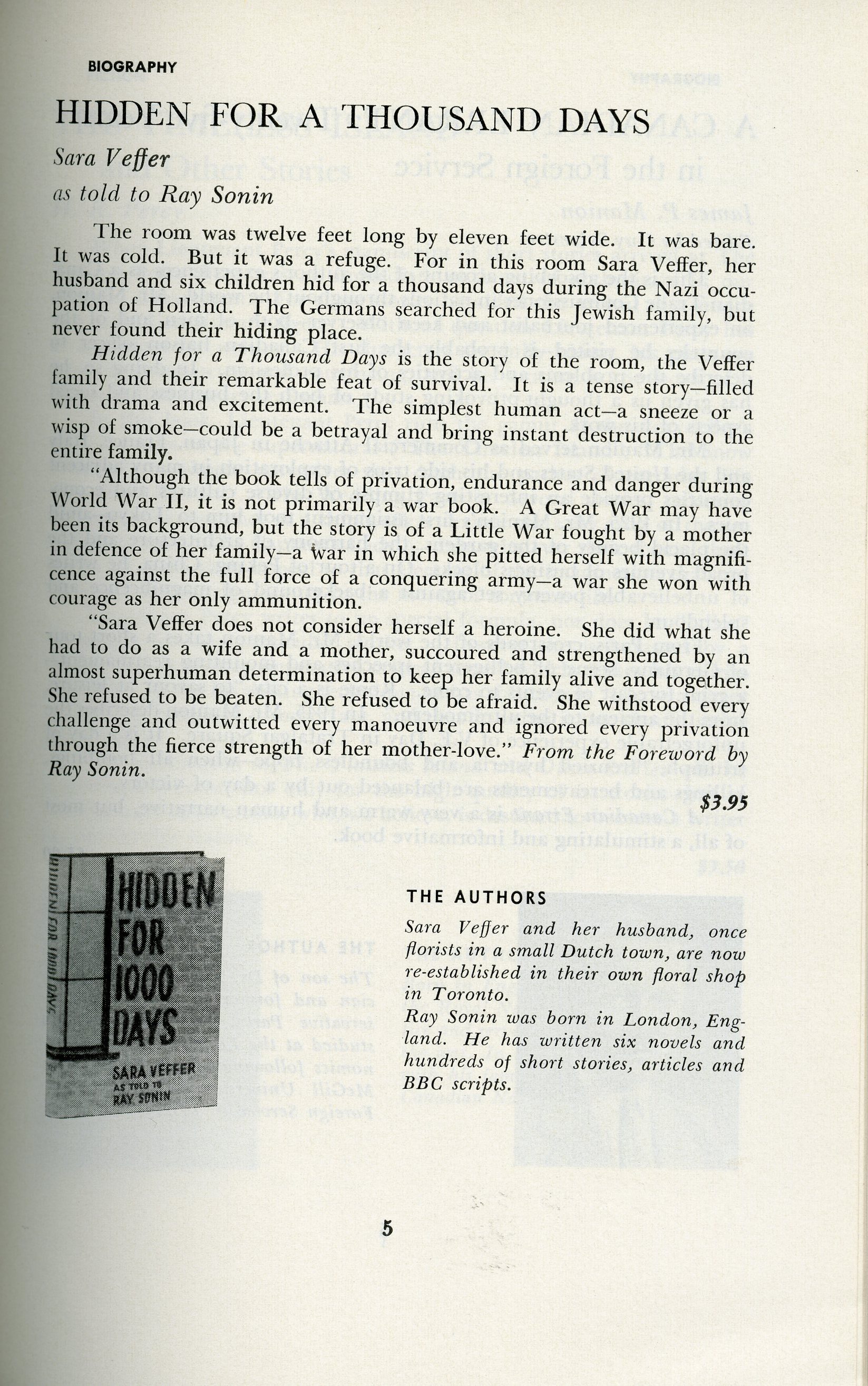

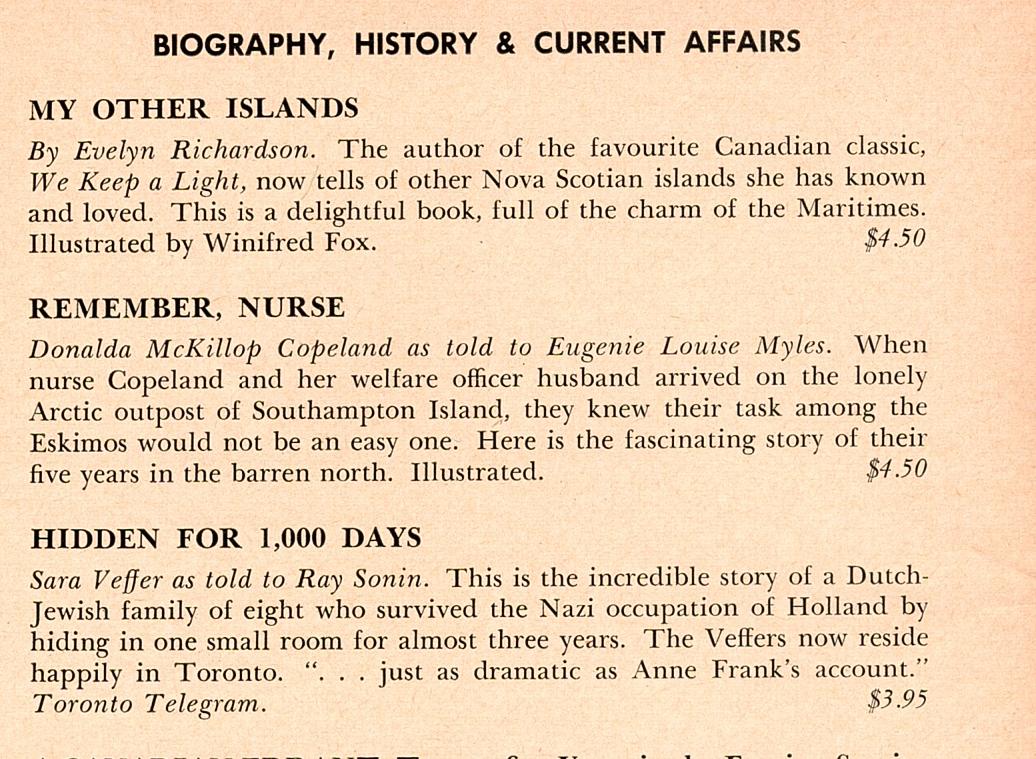

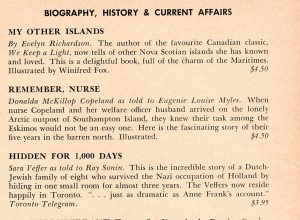

Finally, I explored the publisher’s catalogues, which proved fruitful. Veffer’s memoir was featured in Ryerson Press’s fall 1960 Canadian Publications catalogue with a full page announcement that drew heavily on the foreword by Ray Sonin. A briefer entry appears in the spring 1961 Canadian Publications catalogue, under the broad category Biography, History, and Current Affairs. The catalogue for spring 1961 cites the title as it appears on the dust jacket: Hidden for 1000 Days. Accompanying a synopsis is a quote from a flattering review in the Toronto Telegram: “just as dramatic as Anne Frank’s account.”2

In uncovering something of the publishing history of Sara Veffer’s Holocaust narrative, I hope that I have stimulated further research into the riches of the McGraw-Hill Ryerson Press Collection.

1 See Bryant Fryer, “1,000 Days in Hiding,” Globe and Mail 1 October 1960.

2 See also galileegreen.com/holocaust-memorial-day-and-my-personal-miracle, which features a television episode of NBC’s This Is Your Life devoted to Sara Veffer and her family. The episode was recorded on 8 March 1961 and was broadcast ten days later.